Provence, 1970M.F.K. Fisher, Julia Child, James Beard, and the Reinvention of American Taste

They cooked and ate, talked and argued, about the future of food in America, the meaning of taste, and the limits of snobbery.

Provence, 1970 is about a singular historic moment. In the winter of that year, more or less coincidentally, the iconic culinary figures James Beard, M.F.K. Fisher, Julia Child, Richard Olney, Simone Beck, and Judith Jones found themselves together in the South of France. They cooked and ate, talked and argued, about the future of food in America, the meaning of taste, and the limits of snobbery. Without quite realizing it, they were shaping today’s tastes and culture, the way we eat now. The conversations among this group were chronicled by M.F.K. Fisher in journals and letters—some of which were later discovered by Luke Barr, her great-nephew. In Provence, 1970, he captures this seminal season, set against a stunning backdrop in cinematic scope—complete with gossip, drama, and contemporary relevance.

Luke Barr is an editor at Travel + Leisure magazine. A great-nephew of M.F.K. Fisher, he was raised in the San Francisco Bay Area and in Switzerland, and graduated from Harvard. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and their two daughters.

It was an extraordinary get-together of the leading figures on the American cooking scene. Julia Child M.F.K. Fisher James beard, Richard Onley, Judith Jones and Simone Beck all meeting up and the Child’s vacation home. Luke Barr talks to us about this notable culinary event that he has documented in his book, Provence, 1970.

Books About Food(BAF): How did you happen to hear about this event, or was it something you always knew about?

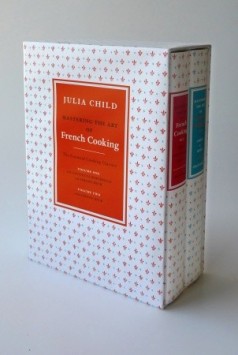

Luke Barr: I’m an editor at Travel and Leisure and I also write for the magazine, so a couple of years ago, I was writing a story about Provence and specifically about Aix-en-Provence which my great-aunt, M.F.K. Fisher, wrote about. I was doing a piece looking at how much it has changed and looking at it through her eyes a little bit, and as I was writing that story, as part of reporting that story, I went to La Pitchoune, which is the house that Julia and Paul Child built on the estate of Simone Beck’s outside of Grasse. This is actually an hour and half’s drive away from Aix, but I just went there, and I visited with a woman who now owns it who is a former student of Simca’s and who teaches cooking classes there.

For my purposes then I was doing the story, and I thought, well, it will be interesting … I’m writing about M. F. K. Fisher and Provence, and she was friends with the Childs, so let me visit their house there where this woman teaches classes, so that’s how I ended up visiting La Pitchoune. Then when I was just researching the Childs and Provence and their house and so forth, I came across this … I just discovered that, oh it’s interesting, my grandmother remembered being there in 1970 and meeting the Childs and so forth and at various points in the 70s.

When I was researching my story, I came across this fact, Oh, they were all there together, and so I wrote that into my story, the Travel and Leisure story that I did about Provence. I sort of mentioned in passing, “Oh, in 1970, interestingly enough, M.F. was here and so were the Childs and so was James Beard and Richard Olney came to visit and Simone Beck was there and Judith Jones and they were all there together.

I remember as I wrote that thinking to myself, “God that sounds like a Vanity Fair story.” You know one of those kind of ‘they were all there together at this particular moment in time’ magazine stories, but then along with my agent, we decided, well this could be a book and so I wrote a proposal, and that’s how it happened. I didn’t know … I don’t think it was a big secret or anything, but I hadn’t heard about it before I wrote the story about my great aunt in Provence.

BAF: That’s interesting, so you were just doing a ‘following in her footsteps’ type of piece.

Luke Barr: She (Fisher) wrote about Provence a lot over her career. A lot of the stuff was for the New Yorker, but then there was also a book that came out in the early 60s that was just about Provence and about Aix-en-Provence in particular. I was just researching that book … Researching a story that was following her footsteps and quoting from that book. She had gone to La Pitchoune in the late 60s while she was working on The Cooking of Provincial France, which was this Time-Life book. It was the first in a series. It had enormous budgets, and everybody …

M.F.K. Fisher wrote the text, the introductory, these kind of loving little mini essays about the different kinds of food in different regions of France, and then there was this guy named Michael Field who was this sort of impressario putting together all the recipes, and they had … Julia Child was an advisor, and James Beard was somehow involved. Basically everybody got on this, involved, because they had these enormous budgets. As part of that, when she was researching the book, she went over and she stayed at the Childs’ house. She hadn’t actually met Julia Child at this point. This was in ’66 or ’67 I think.

Anyway, in 1970, the Childs weren’t there, they just loaned out their house. That’s what they did a lot actually with La Pitchoune. They sort of said to people, “Oh, if you ever need a place to stay in Provence, stay at our place.” A lot of people did that. James Beard stayed there a lot, and so forth. This moment in 1970 that I write about in my book, they were all there together, so the Childs are staying at their house, and my great aunt had rented a house about ten minutes drive away. James Beard, who was really overweight at this point and had signed himself up into this diet clinic in Grasse, which is also ten minutes drive away. He didn’t end up losing any weight, because he was kind of like taking off and going on road trips with M.F. and then coming over to have dinner at the Childs and so forth.

Olney was a very interesting character. He’s actually an American. He lived outside of Toulon, which is also a couple of hours west away from where the Childs were. He came to visit that week before Christmas, and he was a generation younger. The Childs and M.F. and Beard were all in their early 60s at this point in 1970, whereas Olney, who is less well-known but a very seminal figure, he was in his 40s. He wrote, Simple French Food, and The French Menu Cookbook. Those are his most famous works. He was very inspirational. Alice Waters was a sort of protégé. He kind of forged this new, a different style of cooking, very seasonal and a little bit bohemian, and he was a seminal figure. He could be very cruel and impatient, and he was a snob, so he didn’t really like a lot of people. He was a little bit misanthropic. From my point of view, as a character in a book, great to have a character like that because he says bitchy things about people. He seems like he might be the villain of my story, and in a way he is, but he’s also in another way he ends of being kind of like the hero of the piece. In any event, as a writer, it’s great to have someone like Olney in the mix, because he’s causing sparks to fly, which is good for narrative purposes.

BAF: Well, you couldn’t have put together a better cast if you had tried.

Luke Barr: You know, it’s a true story, and I did a lot of research, but when you’re writing this, you want it nevertheless to feel like a novel. I wanted it to read like a novel, and of course I was aided immeasurably by having, like you said, great characters to write about. M.F. is a very sensitive and sometimes brooding writer. Julia is the TV star who is beloved and famous. Beard is also the sort of ebullient and humorous character and struggling with his weight, and then Olney who is the sort of uncompromising and judgmental type. Yeah, that was great.

BAF: Other than, Judith Jones, was there or anybody else able to provide you with first-person accounts of what had happened?

Luke Barr: My grandmother is still alive. My grandmother was there for most of the period that I’m writing about. She knew all these people, so she was really an enormous help, and she also was reading my manuscript as I was writing it and giving me her thoughts, and Judith, also I interviewed her a few different times, and she was great. There are certain things in the book that come directly from her remembering them, various dinners and so forth. Yeah, she was great. She is a great woman.

BAF: How else did you research this?

Luke Barr: Yeah, well here’s the thing. I was very fortunate in my research. There were two key things. One, I didn’t know this, by the way, when I started, or when I sold the book, I just discovered this as I was doing the research, that she (Fisher) was having this long distance love affair with Arnold Gingrich. He was the founding editor of Esquire Magazine. He was a classic sort of New York literary guy who was married, and then M.F. was on the West Coast, but they got into this habit of writing each other a letter every single day, so that continued while she was traveling on vacation.

Her trip to France went for two months or something. She and my grandmother went over there for a long period. During the entire period she was writing these daily letters to Gingrich, and that was absolutely crucial in my research, because it was because of those letters where she would say things like, “Oh well today I’m going to have lunch with James Beard and then we’re going to go down to the Picasso museum and then tomorrow we’re planning to see the Childs for cocktails.” Then the following day there would be another letter that would say, well today we did this and this is how that went and so forth.

I had a very granular, micro-level of detail because of those letters. That was very, very important for my book. I also went through my family’s storage locker, and I found her diary that she wrote when she was in Aurel and Avignon, so that was kind of stream of consciousness writing

BAF: Sounds it. You also went over, in person and did some retracing steps or…

Luke Barr: Yes, indeed. I rented La Pitchoune, the Childs’ house for a month. I was writing and there was one other guy, he was the sort of local chauffeur, a driver back in the 50s and 60s.

When I found him, he’s of a generation that is not on Facebook or is not that easy to track down, but eventually I found him and he was still in Plascassier, the same little town. I thought, “Oh, my God! This is…” and I was so happy and he was a great guy. On the other hand, he would say, “Oh, Julia was great. She was just the most wonderful woman.” So basically all of his anecdotes were… he didn’t have brilliant stories that I hadn’t heard before. It was fun to hang out with him anyway.

The other thing I found when I was there was that the Childs had created this binder that they kept in the house. When you think about it, it’s very common if you’ve ever rented, borrowed someone’s house, like their vacation house, there might be some materials about everything you need to know about how to turn on the heat, here’s how the laundry machine works, here’s the closest place to buy bread or whatever it is. So this is the Julia Child’s version of that and they called it the Black Book. It was just sort of their notes on their favorite place to buy groceries, here’s the complicated way you have to use their oven, here’s the reminder about always put the wicker furniture back. It’s all of their directions, very, very detailed about everything about that house.

Of course, it was totally out of date. Even when I’m looking at it, it’s from the 70s, it had last been updated in the early 80s or something like that. Nevertheless, a fascinating window into the life of the house, the Childs and the way that they lived when they were there. Which is very different than how they were in Cambridge. In Cambridge, she’s a huge TV star and they are constantly busy. Whereas in Provence, she’s on vacation and it’s much more relaxed.

BAF: It must be quite funny to work in that kitchen.

Luke Barr: I know, it was. It was a great place to cook. First of all, because I’m 6’2″….This is one of those ongoing things. I say in my book, that Julia Child was 6’2″ but I’ve definitely had a conversation with Bob Spitz, who wrote the latest Julia Child biography, who told me that actually she was 6’4″. She never said that, she always claimed to be 6’2″. In any event, she was tall. That kitchen is designed for someone who is tall and when you’re, as you would know, when you are cooking, it is noticeable when the counters are a few inches higher. That’s one thing. Another thing was, some of the items that are hanging on the wall are definitely there as almost like museum pieces. Like, “Oh, this is Julia Child’s, whatever, meat grinder that no one is ever going to use.” The knives are all totally sharp, because the woman, Kathie, she teaches classes there so they use all that stuff. Yeah, it was a great place to cook. Not to mention the shopping. The groceries and the quality of the vegetables was just phenomenal.

BAF: Cooking in that kitchen did it give you a greater sense of connection? Did you feel like you were going back in time, that these people were around you at some point?

Luke Barr: Cooking is such an elemental thing that we do together. I really do think that it is a way of connecting us to the past, to traditions and to our families and our loved ones. In that sense, yeah, when I was there, when I was in Provence and I’m cooking, and also anytime that I cook, if I’m following a Julia Child recipe or a James Beard recipe, whatever it is, that act of cooking in a way is a way of connecting us to those people. I certainly felt that as I was writing the book and cooking from all their cookbooks.

BAF: What’s next for you?

Luke: I have a full-time job at Travel and Leisure. I’m editing work on the magazine. I actually do have some ideas kicking around but it’s too soon to talk about them.

Booksaboutfood.com © 2013

“Luke Barr has inherited the clear and inimitable voice of his great-aunt M.F.K. Fisher, and deftly portrays a crucial turning point in the history of food in America with humor, intimacy and deep perception. This book is beautifully written and totally fascinating to me, because these were my mentors—they inspired a generation of cooks in this country.”

—Alice Waters

“Luke Barr conjures the past and pries open the window on a little known moment in time that had profound implications on how we live today. With an insider’s access, a detective’s curiosity, and a poet’s sensitivity, he illuminates a culinary clique that not only changed the way we eat, but how we think about food. Provence, 1970 is as much a meditation on the nature of transition and the role of friendship, as it is on the power of food to unite, divide, and ultimately nourish the soul. For this a ‘non-foodie’ it was a revelation—for the connoisseur among us, it may well be orgiastic.”

—Andrew McCarthy, author of The Longest Way Home: One Man’s Quest for the Courage to Settle Down

“Luke Barr has brought the icons of the food world vibrantly to life and captured the moment when their passion for what’s on the plate sparked a cultural breakthrough. His graceful prose provides a thorough, affecting account of their talents and reveals how their disparate personalities defined the very essence of French cuisine.”

—Bob Spitz, author of Dearie

“Brilliant conversation, dimmed lights, culinary intrigue, urchin mousse, a glass of Sauternes . . . Luke Barr has written one of the most delicious and sensuous books of all time. It brims with love of food and wine.”

—Gary Shteyngart, author of The Russian Debutante’s Handbook and Super Sad True Love Story

“Luke Barr has written a lovely, shimmering, immersive secret history of an important moment that nobody knew was important at the time.”

—Kurt Andersen

“Luke Barr has written a wonderful, sun-dappled account of the pleasures of cooking and eating in good company. With the deftest of touches, he describes a gathering of celebrated chefs—including Julia Child, his great-aunt M. F. K. Fisher, James Beard, and Richard Olney—and the way their American palates transformed French culinary rules for a homegrown audience. Both a meditation on the power of friendship and the uses of nostalgia, Provence, 1970 is the kind of book you want to linger with as long as possible.”

—Daphne Merkin

“Luke Barr paints an intimate portrait of the ambitious, quarrelsome, funny, hungry pioneers who brought about a great culinary shift—the ending of the classical era, and the beginning of a newly experimental, wide-ranging, ambitious cuisine, one that was inspired by France but was quintessentially American in style and flavor. Provence, 1970 gives a front-row seat to the creation of modern American cooking.”

—Alex Prud’homme, co-author with Julia Child of My Life in France

All Alone: December 20, 1970

M. F. K. Fisher walked into the lobby at the Hotel Nord-Pinus in Arles trailed by a bellhop.

Famously beautiful in her youth—she’d been photographed by Man Ray, and peered out glamorously from her book jackets—M.F. was still a striking woman. Her long gray hair was pinned up in an elegant twist at the back of her head, her eyebrows were pencil thin, and she was dressed in a tailored Marchesa di Grésy suit and a wool overcoat. She made her way to the front desk to check in. The decor was Provençal rustic, almost cliché, with tiled floors and wrought-iron chandeliers. She’d been here years ago, and it hadn’t changed a bit. Her heels made echoing noises in the empty lobby. It was the week before Christmas 1970, and the weather was unusually cold. She had the distinct impression of being the only guest at the hotel. The place was a tomb.

The tall man at the front desk was vaguely hostile. He was sullen, but, then, that seemed to be the default posture of French service personnel in general, at least when it came to Americans during the off season. Veiled contempt. He explained that the room she had written ahead to request—one facing the Place du Forum—would be too cold at this time of year. He did not apologize for the lack of heat, he simply stated it as a fact.

She asked to see for herself, and he was right: the heat was off in that part of the hotel, which was noticeably colder. And so she chose a room at the back of the building, on the first floor. It was named for Jean Cocteau (there was a small brass nameplate on the door), and inside was the largest armoire she’d ever seen. It must have been twelve feet tall. It was grotesque, she decided, but she liked it for the audacity of its scale.

The bed was comfortable, so there was that.

She unpacked her things, three suitcases’ worth, clothes for every occasion and weather, multiple pairs of shoes, books, and assorted papers, all of which fit easily in the enormous armoire. There was a writing table and a chair, and a photograph of Cocteau on the wall. She sat for a moment in the silence of the suddenly foreign room, looking at the quaint toile de Jouy wallpaper, and then withdrew from her purse a new notebook—small, pale green, spiral-bound. On the inside cover, she inscribed the words

WHERE WAS I?

in underlined capital letters. Where was she indeed? And why? She’d spent the previous weeks in the mostly pleasant company of family and friends, having traveled from Northern California to southern France with her sister Norah Barr, and then finding herself swept up in an epic social and culinary maelstrom, which seemed to involve everyone who was anyone in the American food world. Julia Child and her husband, Paul. James Beard. Simone Beck and her husband, Jean Fischbacher. Richard Olney. Judith Jones and her husband, Evan. Together they had cooked and eaten, talked and gossiped, and driven around the countryside to restaurants and museums and to the incredibly beautiful chapel that Matisse designed in the late 1940s.

She had left all that behind at the crack of dawn this morning. Raymond Gatti, the local chauffeur she knew well from a previous trip, had picked her up in his Mercedes and delivered her to the Cannes train station, telling her repeatedly that they would be far too early for the ten o’clock train. But she didn’t care. She preferred to be early: she had a great fondness for leisurely hours in train station cafés. And most of all, she was eager to get away and be on her own. She needed to write, think, and figure out what she wanted.

In her new journal, underneath WHERE WAS I?, she wrote:

I am in southern France, and it is December, 1970 and I am 62 1/2 years old, white, female, and apparently determined to erect new altars to old gods, no matter how unimportant all of us may be.

The “old gods” were French, of course. They were the gods of food and pleasure, of style and good living, of love, taste, and even decadence. M.F. had spent the last thirty-odd years writing a kind of personal intellectual history of these ideals in her books, memoirs, and essays. These works were her “altars,” so to speak, and she was now embarked on a new one. This notebook would serve as the site of her daily communion with France.

France had long been at the center of her philosophy. She had made France a touchstone of her writing, in which she alchemized life, love, and food in a literary genre of her own invention. But she was suddenly keenly aware of the need to make new sense of the old mythologies. The events of the previous weeks had shown her the limitations of her own sentimental attachments—to the past, to la belle France—and confronted her with the too-easy seductions of nostalgia, the treacheries of snobbery.

She was alone in Arles for a reason. It was a reason she was still in the process of formulating.

The next day, M.F. wandered the cold streets, pushing against the wind, looking for a place to eat. The town was closed for the season. fermeture annuelle, read the signs on every restaurant, including, most unforgivably, the restaurant and bar in her own hotel.

The tall and less-than-friendly front desk clerk told her this without looking up. “Rat bastard,” she thought. This occurred with some frequency: she would swear to herself, fuming at an irritation while outwardly maintaining an air of dignified, steely calm. There was the man at the American Express ticket office in Cannes this morning, for example, who had issued her a ticket for a nonexistent train to Arles. She’d returned to the office, and he had impassively explained that she was surely wrong, then looked at the schedule and discovered he was wrong, and blandly handed her back the ticket and said she could take the next train, in a few hours. “Too bad,” he said, diffidently. “You rat bastard,” she thought. “You damned rat bastard.”

And now the hotel clerk and his closed-for-the-season restaurant and distinctly unsympathetic attitude. She asked where she might find something to eat. She spoke excellent French, but had an American accent; he replied in French.

“Oh, a dozen places,” he said idly. “Jean will indicate them whenever you wish.”

“I am hungry now,” she replied.

“Jean!” he said. Jean turned out to be a teenager in a thin, dirty white jacket whose long blond hair whipped in his eyes as he stepped outside and pointed the way.

“Go down to the big boulevard. Turn to the right. They’re all there, quantities of them!” He ran back into the warm hotel.

The sidewalks were icy. M.F. passed by a couple of gypsies playing intense, dramatic guitar music, and eventually made her way to a brasserie on the other side of town, after a half-hour walk. She ordered mussels, followed by pieds et paquets—long-cooked stuffed and rolled lamb tripes—and sat reading Le Provençal and drinking a gin and red vermouth. She watched the room, mostly young men in groups or older men reading the local paper and eating alone. None of them seemed to notice her presence. She felt perfectly invisible.

That night, she wrote in her journal, describing the Provençal locals:

They have a haughty toughness about them, with possible anger and suspicion not far back of their outward courtesy. When I go into a restaurant or a bar, I am given a table when I ask for it, and I am brought what I order to eat and drink, and when I ask for the bill, I am given it, but there is never even a pretense of interest in whether or not I like my table, my meal, whether or not I want to drop dead right there. Good evening, yes, no, goodbye.

M.F. herself had a haughty toughness about her. Indeed, she had embarked on this solo expedition to Arles as a kind of challenge to herself. To travel alone, to see Provence as it really was rather than as she imagined it to be, to compare her fond, nostalgic recollections of the place with its immediate, cold reality. And more than that: to make sense of her life, and what the future held. Her children were grown. She could feel the past slipping away. She wasn’t quite sure what she wanted of the future.

She lay in bed unable to fall asleep, too aware for comfort—her mind racing, her perception over-keen, every distant sound amplified tenfold in the dark. The bells from St. Trophime; the sudden roar of a car engine on the road outside.

She watched the light and shadows on the ceiling plasterwork. There were no spiders or large insects to be seen in the half-light, thankfully. Only the other night, in the apartment she’d rented in La Roquette sur Siagne, near Cannes, a many-legged creature had dropped from the ceiling and landed on her forehead. Without missing a beat, she’d flicked it onto the floor, then lit the lamp and watched it cautiously unwind itself and cross the tiles to the safety under the couch. Even as her heart beat in her chest, she felt strangely sympathetic toward the thing—it must have been as shocked as she’d been to find itself stranded on her forehead. She was reminded of another night not so long ago at her friend David Bouverie’s ranch in California. She’d been put in a little-used guest room, and one of the cats, accustomed to sneaking through the open window and onto the bed, leapt onto her, the unexpected human lying there under a sheet. She kicked intuitively in the pitch dark, and just as intuitively, the cat sank all its claws into her like wires and then leapt with a horrified moan out the window. She went back to sleep. In the morning, the sheets were streaked with blood from more than a dozen neat little pricks in her skin.

Days went by.

M.F. took long baths and drank cafés au lait and set off into town through the pre-Christmas crowds and past shutters closed tight, behind them warmth and family life. She found herself carrying on interminable interior monologues, all in the form of sentences and paragraphs, and often in the third person. “She looked into the glass-thickened air of the café,” for example. Or she would give herself practical instructions: “Mary Frances, go to the toilet while you know where it is.” She was detached: a ghost, observing the town, its people, herself. There but not there. She was hungry all the time, always in search of a decent, open restaurant, and never quite satisfied. She recorded it all in her notebook.

It was ironic. Here she was, the great chronicler of food and love, of appetite and longing, hungry and alone. And furthermore: hungry and alone in France, of all places. It made no sense. This was, after all, the place that had reliably inspired her to eat, and to love.

Again and again, M.F.’s thoughts returned to the lunches and dinners with the Childs, Beard, and Olney, and her friends Eda Lord and Sybille Bedford, whom she had been visiting at La Roquette: one feast after another, the wines, terrines, roasted chickens and jambon persillé, leek and potato soups, and apple tartes tatins. And the gossip, talk, and more talk, comings and goings, trips to town to mail letters and pick up baguettes and groceries, country excursions and impromptu lunches. In the background, all the while, had been a growing sense that they were all on the cusp of something new—a new decade, a new era. It was a moment of flux, of new ideas. But what that meant for each of them was less clear. For M.F., the very meaning of taste and sophistication was in question—as was the viability of the literary voice and persona she had cultivated for nearly four decades.

It was the arrival of Richard Olney, just before Christmas, that had crystallized the contradictions of the moment; he had spurred her sudden departure.

Now, in Arles, it seemed to M.F. almost comical, the sudden change in circumstances. From feast to famine, so to speak. And it had been entirely her own doing! There she had been, in the hills above Cannes, surrounded by warmth, friends, and sustenance, and here she was in Arles, cold and alone.

Why had she left?

Leave a Reply