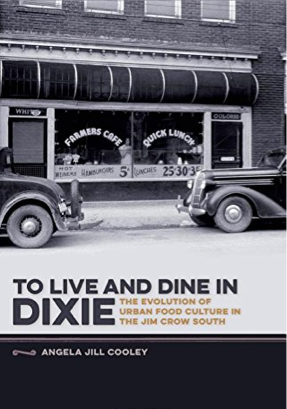

To Live and Dine in DixieThe Evolution of Urban Food Culture in the Jim Crow South

This book explores the changing food culture of the urban American South during the Jim Crow era by examining how race, ethnicity, class, and gender contributed to the development and maintenance of racial segregation in public eating places. Focusing primarily on the 1900s to the 1960s, Angela Jill Cooley identifies the cultural differences between activists who saw public eating places like urban lunch counters as sites of political participation and believed access to such spaces a right of citizenship, and white supremacists who interpreted desegregation as a challenge to property rights and advocated local control over racial issues.

Significant legal changes occurred across this period as the federal government sided at first with the white supremacists but later supported the unprecedented progress of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which—among other things—required desegregation of the nation’s restaurants. Because the culture of white supremacy that contributed to racial segregation in public accommodations began in the white southern home, Cooley also explores domestic eating practices in nascent southern cities and reveals how the most private of activities—cooking and dining— became a cause for public concern from the meeting rooms of local women’s clubs to the halls of the U.S. Congress.

Angela Jill Cooley is an assistant professor of history at Minnesota State University, Mankato. She has a PhD from the University of Alabama and a JD from the George Washington University Law School.

“I cannot overstate how useful it is that Cooley is trained both as a cultural historian and as a lawyer. The richness of analysis in To Live and Dine in Dixie comes from the interplay of methodologies from both fields. Few other scholars can bring such research tools to the subject.”

—Elizabeth Engelhardt, author of A Mess of Greens: Southern Gender and Southern Food

“To Live and Dine in Dixie is an important addition to the canon of southern history and food studies.”

—Marcie Cohen Ferris, author of The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region

Urban authorities worried that eating places might provide public space for acts of supposed moral degradation, especially drinking. After Atlanta’s city council ended food service in local saloons, eateries established pushbutton systems with nearby saloons so that patrons could continue to have a drink with their meals. When Jim Brown, a Greek café owner in Atlanta, wanted to order drinks for a patron, he pushed a button to contact the saloon and placed the order. Every restaurant in the city reportedly used a similar system until 1906, when the city council prohibited restaurants from serving alcohol. Officials enforced this ordinance by refusing business licenses to restaurants located near saloons.

The struggle that southern cities had to reconcile eating and drinking in public places reveals the complicated merger of various value systems in a diverse urban environment. The governing, salaried classes worried that working- class whites, African Americans, and foreigners might use these spaces as unregulated saloons. If drinking were allowed, an assortment of patrons of both sexes might linger in restaurants, becoming intoxicated and perhaps indulging in further public immorality and debauchery. City councils worried especially about eating places frequented by lower- class whites and African Americans.

The desire to separate eating and drinking by restricting alcohol service in restaurants had class and racial implications. In Atlanta, for example, the city council admitted that a new regulation against drinking in restaurants specifically targeted black establishments. Nevertheless, the broad ordinance covered all public eating places. This more general application caused some white councilmen to initially oppose the law. One council member argued that men who did not frequent saloons nevertheless drank alcohol with their meals and joked that restaurant service “was the only way the prohibitionists could get a drink.” The mayor opposed its wide applicability, stating that “there can be no harm in serving beer in such [eating] places as are in the center of the city [where the white restaurants were located].” Despite such protests, the council passed the law unanimously.27

Atlanta also tried to do away with alcohol entirely. One month after it took alcohol out of city restaurants, the Atlanta city council closed the city’s saloons and limited the purchase of alcohol to a low- alcohol beverage nicknamed “near beer.” The mayor recognized the incongruence of this action, commenting in late 1906, “The council recently refused to license certain restaurants because they were next door to saloons and then later closed up the very saloons which adjoined the objectionable restaurants.”28 For Atlanta, prohibition represented only the latest in a series of legislative attempts to govern the use and sale of inebriants in the city. The discourses Southern Cafés as Contested Urban Space and actions surrounding these events reveal white middle- class anxieties over the consumption of alcohol in public spaces. But despite the council’s best efforts, closing the saloons failed to solve the problem of drinking in public eating places and encouraged the emergence of cafés intended to circumvent the laws. Atlanta authorities continued to spend time and energy regulating the sale and consumption of alcohol in public eateries. The city licensed near- beer purveyors. Atlanta went through various stages of prohibition and temperance in attempting to end crime and disorder in public spaces.

In the absence of traditional saloons, many observers considered lower class eating places to be fronts for the service of alcoholic beverages, legal or otherwise. White middle- class authorities, some of whom no doubt served whiskey at home, believed eating places that continued to serve alcohol attracted lower- class elements and that this combination led to trouble. In 1908, two years after Atlanta closed its saloons, the local columnist J. Francis Keeley noted that he would rather see “a respectable saloon than a so- called café, selling ‘near beer’ and given to rowdyism.”29 Although the city passed more prohibition laws, authorities continued to struggle with eating places and near- beer saloons that sold alcohol illegally or served near beer to their customers in contravention of local licensing provisions.

Controversy stemmed from these attempts to ban a substance that had a long connection with consumption and eating. In Montgomery the connection between eating and drinking alcohol was so common that proprietors assumed that having a business license to serve meals also allowed them to serve alcoholic beverages. In 1875 the Montgomery authorities convicted a local restaurateur named Nicrosi for selling alcoholic beverages without a license. Nicrosi apparently sold drinks to patrons eating on- site and argued that his restaurant business license implied the ability to serve alcohol with meals. The Supreme Court of Alabama disagreed and affirmed Nicrosi’s conviction, but this did not end the controversy.30 In 1904 Montgomery’s chief of police complained that a local ordinance allowing restaurants to conduct business on Sunday enabled the sale of alcohol despite laws against the practice. The connection between the sale of food and drink was so strong that the city’s blue laws were threatened “where saloons are allowed to have restaurants attached and keep open all day Sunday to serve meals.”31

The struggles of urban areas such as Atlanta and Montgomery reveal the difficulties of regulating morality in eating establishments. Drinking in public spaces, illegal or otherwise, led to other alleged moral infractions. Alcohol in public spaces often coincided with sexualized conduct between men and women. Again, cafés served as sites for these alleged transgressions. Unlike the higher- class restaurants and their ladies’ cafés, quick- service eateries did not separate men and women. In fact, the ability to interact with the opposite sex might have been an enticement for some patrons, as it was for Joe Christmas. These spaces offered opportunities for men and women to meet, mingle, converse, and engage in sexualized activity that encompassed everything from drinking together to public displays of affection to sexual intercourse.

Atlanta police often raided cafés to halt sexual interactions considered to be improper. In May 1914 the College Inn was the site for such a raid. Its proprietors faced charges related to illegal drinking and sexual mingling. The judge accused the café of circumventing local prohibition laws by purchasing near beer from black merchants, who delivered drinks to the College Inn in violation of city ordinances. Worse still, men and women reportedly drank together at the College Inn, leading to a variety of different types of “disorderly conduct.” Among other things, reports indicated that women sat in the laps of male companions and “embraced” them.32 These eating establishments violated local laws and cultural conventions that attempted to control sexualized conduct in the public sphere by separating men and women. Unlike ladies’ cafés, these eateries failed to respect these principles

in favor of more liberal interactions among men and women. In addition to the relatively innocent intermingling of the sexes in legitimate eating places, southern authorities worried that an eatery could serve as a front for a brothel. In 1903 black prostitutes arrested on vagrancy charges in Atlanta inevitably reported working at “Old Lady Brown’s Restaurant.”

Sarah Brown, a sixty- year- old African American woman, operated a café that authorities assumed was a front for prostitution. Police often visited her establishment for unspecified complaints of “disorder,” and reportedly “drunken men [visited] at all hours of the day and night.” Brown’s café was located on Decatur Street, an area of Atlanta notorious for drinking, prostitution, and other vices. She reportedly hired around forty women to work at Southern Cafés as Contested Urban Space 57 her restaurant. In 1900 Atlanta authorities had charged Brown with running a disorderly establishment. The judge let her go with the promise that she would keep her customers in line. Despite this warning and the apparent illegal activities undertaken at Brown’s café, there is no evidence that police shut her down. But the police did begin arresting any woman who reported working for Brown on “vagrancy” or prostitution charges.33

The fact that Brown hired African American women as supposed waitresses illuminates another complicating factor with regard to public spaces designated for eating. For white southern authorities, the potential for race mixing in quick- order public eating establishments increased the potential threats associated with illegal drinking and illicit sexual interaction.

Although southern eating places tended to implement some form of racial segregation even before formal Jim Crow laws, interracial interactions nevertheless took place. The fact that many café proprietors came to the American South unfamiliar with the region’s racial mores may have increased the threat to white supremacy. Albert P. Maurakis, the son of a Greek café operator, recalls his confusion over racial segregation when he moved from Pittsburgh to Danville, Virginia. He relied on family members with longer tenures in the South to elucidate the region’s racialized eating rituals. He recalls, “Uncle Steve explained the Southern Jim Crow practice of segregating the races in the use of all public facilities and that the ‘colored’ must enter back doors to eat in restaurant kitchens.” The Maurakis family acquiesced to segregation culture. Although his uncle’s restaurant had no rear entrance, he served black customers through a window. When Maurakis’s father opened the Central Café, he included separate entrances and an eight- foot partition to separate the black and white dining areas.

Leave a Reply