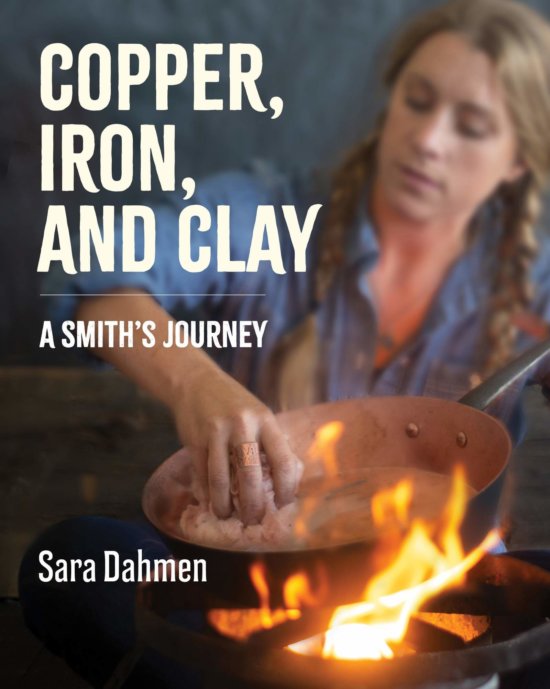

Copper, Iron, and ClaySara Dahmen

A gorgeous, full-color illustrated love letter to our most revered cookware—copper pots, cast-iron skillets, and classic stoneware—and the artistry and workmanship behind them, written by an expert craftsperson, perhaps the only woman coppersmith in America.

Today, most people are concerned about eating seasonal, organic, and local food. But we don’t think about how the choices we make about our pots, pans, and bowls can also enhance our meals and our lives. Sara Dahmen believes understanding the origins of the cookware we use to make our food is just as essential. Copper, Iron, and Clay, is a beautiful photographic history of our cooking tools and their fundamental uses in the modern kitchen, accompanied by recipes that showcase the best features of various cooking materials.

Interested in history and traditional pioneer kitchens, early cooking methods, and original metals used in pots during the early years of America, Sara became obsessed with the crafts of copper- and tin-smithing for kitchenware—specialty trades that are nearly extinct in the United States today. She embarked on a journey to locate artisans nationwide familiar with the old ways who could teach and inspire her. She began making her own cookware not only to connect with the artisanal traditions of our nation’s past, but to adopt the pioneer kitchen to cook and eat healthier today. Why cook fantastic, healthful food in a cheap pan coated with toxic chemicals and inorganic elements? she asks. If you buy one high-quality item made from natural materials, it can serve your family for generations.

Richly illustrated with dozens of stunning color photographs, Copper, Iron, and Clay showcases each material, exploring its fascinating history, fundamental science—including which elements work best for various cooking methods—and its practical uses today. It also features fascinating interviews with industry insiders, including cookware artisans, chefs, entrepreneurs, and manufacturers from around the world. In addition, Sara provides recipes from her own kitchen and some of her famous chef friends, as well as a few historical favorites—all which are optimized for particular kinds of cookware.

Sara Dahmen is the founder of House Copper & Cookware, a line of American-made cookware created with pure, natural materials and the help from local family-owned companies. Her cookware has been featured in national and international publications such as Cooking Light, Food and Wine, Veranda, Beekman 1802, Root+Bone, Midwest Living, and many more.

One of the only female coppersmiths in America (if not the only), Sara has had a varied career, from her first job in marketing to building an award-winning wedding planning business to writing historical fiction. Her love of deep historical research led to her current work as a metalsmith of vintage and modern cookware.

Sara has been published as a contributing editor for trade magazines and recently spoke at TEDx Rapid City. Sara is also the co-founder of the American Pure Metals Guild and is an apprentice to a master tinsmith in Wisconsin, where she works with tools from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to rebuild vintage cookware and design custom work from scratch. When not working in her garage, she can be found writing historical fiction, sewing authentic clothing for reenactments of frontier days, and hosting epic historical-themed dinner parties. She lives in Port Washington, Wisconsin, with her husband and three young children.

Sara Dahmen

![]()

An accomplished author of historical fiction turns her talents to the art of coppersmithing. Not the usual career move one might take. For Sara Dhamen it has been the natural way to go.

Sara was kind enough to literally step away from her workshop and talk to us about her fascinating new book Copper, Iron, and Clay

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

BAF (BooksAboutFood.com: You certainly have one of the more interesting job descriptions I’ve heard in awhile.

Sara Dahmen: It’s different.

BAF: I guess there’s not a lot of women in your line of work?

Sara Dahmen: No. I have yet to meet another woman building copper cookware. I’ve met a couple women who are tinsmiths. They specifically work in tin sheet metal. There’s two around my age around the east coast. Annie is up in New York, and Jenny is in Colonial Williamsburg, and that’s kind of it for those that do it like a job.

But nobody does it in copper that I can find. It’s the weirdest thing. I mean, it was traditionally a guy’s thing. It was passed on specifically, father to son, or uncle to nephew. It was really kept in the male line in the family. Even to the point where the last book on coppersmithing, which was published in the 1890’s, in the introduction, the author said his dad specifically told him never to share what he’s about to share, because it’s meant to stay in the family.

And he’s like, but for posterity’s sake, something has to be written somewhere, or we could lose this knowledge. And funny enough, we almost did lose it. And his book is like the last time anyone’s talked about coppersmithing until now, until copper [inaudible 00:02:01]. And honestly, even reading the coppersmithing book that Fuller put out, you have to have already been making copper cookware for years to even understand what he’s talking about in the book, because it’s so dense. So it’s like, useless tome for any beginner anyway.

BAF: The first rule of tinsmithing, don’t talk about tinsmithing.

Sara Dahmen: Yes! That’s exactly it.

BAF: I just want to touch on something. You said the last book that was published was in the 1890’s?

Sara Dahmen: Yeah.

BAF: Did you mean the last book you’ve read? Or literally, the last book that was put out there?

Sara Dahmen: No, that was the last … The last book I can find on coppersmithing, which is obviously my passion was by John Fuller, Sr. And it was last published 1894.

BAF: You take it for granted these crafts that were so in use would just keep going. But then, when you realize a book was published over a hundred years ago, kind of brings it all to perspective, we are possibly losing some of this stuff.

Sara Dahmen: Oh, we totally are. I mean, even the tin smiths that I worked with that I kind of learned a lot of the trade from, they really work mostly in tin. But the same rules apply for sheet metal work. You know, they still are sitting there, and they’re like, “Okay so, this is how we create a pattern when you’re looking at an old vintage piece.”

They’re all retired, usually they’re mechanics and stuff. But they still are piecing together how to do things, because so few of them have the actual knowledge. It’s really disappeared in less than a hundred years. It’s really disappeared, because we’ve moved so much of our production offshore, and we’ve mass produced. And we no longer know the steps to building things we use every day in our kitchen, which is kind of sad.

BAF: So, it’s almost like the retro fitting their knowledge, so to speak.

Sara Dahmen: Right.

BAF: I think the big question is, how does a woman who writes historical women oriented, historical fiction, move into the ‘obvious’ transition of being a coppersmith?

Sara Dahmen: It was complete serendipity. And it was certainly not planned. It’s not like somebody wakes up one day and goes, “You know what, I can’t wait to be a coppersmith.”

BAF: OkayI wasn’t sure about that.

Sara Dahmen: Yeah, right? No, no, it really was … And I do touch a little bit about this in the book. It’s why my introduction to the book is so long. But it really was me researching for historical novels. And I had already started to build a cookware line, because I had been writing historical novels, and I realized so much of what I was talking about that all these women used in the kitchen. These women, our great grandmothers, could walk down the street and get their pots fixed.

They could go to the blacksmiths and get a handle that fit for a pot that they were keeping in the family, or something like that. And so much of that had disappeared. And I was like, “Well, that’s ridiculous. We should be making that here in the U.S. still.” And I started to build American … I wanted everything sourced as local as possible in America. Just like the old days. Anything you would have found in a pioneer kitchen.

And in the process of doing the book research, doing the research to build a cookware line, just like in my historical books, I stumbled upon one of those tinsmiths who happens to be one of the best in the country Bob Bartelme is about 15 minutes from my house. And he had me show up and watch him build a piece of cookware. Just a like, he was like, “Oh, this is a standard” … I don’t remember, revolutionary war tin pot that every soldier had in the rev war. Just exactly like it.

And he’s like, “The next thing, you should come and build one yourself.” So I did. An then he said something along the lines of next time, you should build something out of copper. And I was like, hell yeah, that’s what I really want to know.

And so then, he had me show up again. And it became one of those things where I kept showing up multiple times a week, bringing my kids once we realized they could be trusted with all the tools, and so I could come even more. And then, he just started to introduce me as his apprentice. And it’s been over four years that I’ve been doing that. I’ve been going up to his shop on average, twice a week. And in fact, I’m going up tomorrow. I’ll take the kids, and away we go. And my daughter’s already trying to build little tiny pots and pans. And you know, and it just is, it became a very organic thing, but a very much an apprenticeship in the way of the old school apprenticeships.

We spend our holidays with him and his wife, versus our parents. You know, like we almost moved in as part of the family, the way apprentices used to. They would move in. You know, like the book Johnny Tremain.

BAF: Wonderful book.

Sara Dahmen: He’s an apprentice. He’s a silversmith.

Yeah, but he lives with the family. He eats with the family. He celebrates all the experiences with the family as he learns. And it’s kind of almost the same thing in a modern sense. We celebrate Christmas Day with Bob and his kids and grandkids. It’s become an apprenticeship in the truest sense of the word.

And I’m still learning from him. I still screw up. Though now, I do more copper, he does tin. So sometimes, he gets stuff he gives to me, because I’ve spent more time on copper than he has. So I have a different kind of knowledge base with the metals than he does.

So it’s kind of cool the way it’s worked out.

BAF: Maybe just touch a bit on your cookware line you mentioned.

Sara Dahmen: It’s called House Copper, because copper is kind of the cornerstone of our line. And obviously, what I spend the most time making for part of the line. But I really, I wanted to have a battery of what every woman had in … It was women, let’s be real … every woman had in the kitchen as we built our country. So, it’s some cast iron, some pottery, crocks and bowls, and some copper pots. And I did copper because copper existed back then, but also because most people had tinware instead of copper, unless you were wealthy. And that’s just not sustainable in today’s kitchen. So I could modernize the copper cookware.

Wood spoons and cotton towels, just everything you would have found in a pioneer kitchen, all sourced and made within the U.S. Almost all of it’s Midwest, because I’m in Wisconsin. So, that’s what it is. And it’s super kind of the basic stuff. Once you get it, you really should never need to replace any of that cookware, and pass it on down. Never have to fill a landfill. Put it in your will, and carry on with a handful of pieces. So that’s it.

BAF: So everything you make could be found in your (fiction)books.

Sara Dahmen: The goal is, is that, it lives beyond you. You’re always, if you’re going to be a builder, you want something that will last for posterity. So you know, you build it for your kids and your grandkids kids. So that’s kind of the fun. You know, every time I sit and I’m kind of annoyed with the buffing wheel, and I’m really tired of doing copper work for the day, I think to myself, everything I’m building, obviously the iron will rust faster than … You know, copper doesn’t rust. But every copper pot I’m working on has a good chance to show up in an archeological dig somewhere thousands of years from now because it’ll last that long. You know, like they’ll find it and be like, “This is what they cooked in in the 2000’s.”

That’s just how long it lasts. And it’s worth putting your time into something like that. I think, anyway

BAF: I’ve been in restaurants where they’ve had copper cookware on the walls as decoration. And I’m thinking that could be fixed. That could be redone and reused.

Sara Dahmen: Yep.

BAF: People often think of copper as being a high maintenance thing to cook with. What would be the advantage of copper?

Sara Dahmen: The first thing I say when anyone say that it’s hard to take care of, my answer is it is the exact same amount of work as a cast iron skillet. And the reason is is because, you have to season a cast iron skillet. You have to hand wash a cast iron skillet. You have to, you take care of it, right?

Well, copper, you don’t have to season. You do have to hand wash. And instead, you have to occasionally polish it. You don’t have to season it, you just have to occasionally, if you like it shiny, polish it. If you don’t like it shiny, you can use it like any other cookware.

If it’s lined with tin, every 12 to 15 years, you can have it relined. Longer if you don’t use it every day. Decades, if you don’t use it every day. So, it’s really the same amount of work. Sometimes in a way, even less than cast iron in terms of taking care of.

So, that’s kind of like, that’s not … Once you understand the differences, it’s like, it’s not even a point. But the advantages of working with copper is, you have extreme control over your heat. So if you’re not just frying something up, and you’re not just searing a steak like you do in cast iron, you’re actually able to completely control the temperature, both in terms of how hot you want something, how long you want it to cook, and how quickly it cools.

There’s whole things on making beer the old fashioned way, and even making cheese. There are certain types of cheese, like Gruyere, it’s not even considered cheese unless it’s made in a copper vat. Like, because of the process and the way that it has to heat and cool so precisely in order to be the right kind of cheese. And then you can get into copper ions and stuff. But really, it comes down to the temperature control. And that’s the same for anything.

Essential oil makers use huge copper stills. And I actually just got asked to make one, to make some. Because they want somebody based in the U.S., because I can say exactly, my tin is lead free. I get it from Iowa. It’s not coming from a country where they’re like, “It’s lead free.” No, it’s not.

BAF: Sounds like a fascinating project, and slightly off topic. But for a craftsperson to be given that challenge, it must be kind of exciting, and daunting.

Sara Dahmen: It is, and yeah, that’s the beauty of it. It’s always a challenge, right? And it’s fun. It’s fun to figure out how to build something. Even like tomorrow, I have to make a very customized goat pail for goat milking that someone wants. And it’s like, they want a flip lid that only flips up half. And then a spout, and then a bail. And it only has to be two quarts. And all these things, and it’s like, “Um, sure, give me a couple months.”

BAF: That’s what keeps you so busy.

Sara Dahmen: Yeah, it really does.

BAF: You’ve written, obviously, before, but this is a totally new writing project for you, I can imagine. Was it hard to slip from historical fiction to an autobiographical crafts-orientated book. Was that a difficult transition?

Sara Dahmen: Yeah. It was. To be totally and completely transparent, first of all, I never planned to have my personal story in this book. I went kicking and screaming to put it in. I was like, I am 35. This feels like a memoir. I am too young to write a memoir. This is stupid. I don’t want to do it. Nobody’s going to care. My agent was pushing, my editor was pushing. My other editors, it was like, they were like, “No, you have to put your story in because it kind of explains why you’re the one telling this story, versus anybody else.”

And I was like, “That’s fine, but I just … ” And they were like, “No, no, more story, more story, more story.” And that’s again, why there’s this really long introduction. And the original version of this was me wanting to basically do this, The art of a coppersmith…bringing that knowledge back in a modern book.

So, the original book was called An Education In Cookware. It was so boring and so full of facts, I fell asleep writing it. I would fall asleep at my computer while writing the chapters, because it was so much fact. And my mom was like, “You know, you can put people to sleep with this stuff.” And it’s like, “Yeah, I noticed.”

So, it went through many renditions.

BAF: Too academic?

Sara Dahmen: It was really academic. And my agent kind of finally said, “Sarah, about seven people in the country will care about this, if it’s written this way.” And she was right. Of course she was right, she’s my agent.

But it was different. It was hard because in fiction, you get to play so much, and you don’t have to follow rules. You don’t have to be specific about recipes and tablespoons. You don’t have to make sure that you fact check, and then fact check again. And there was an outline! I never write my fiction books from outlines, ever. I hate writing from outlines, first of all. But I never do it for fiction.

There was an outline I had to follow. It was again a challenge which was good. Normally, if I have a fiction book that I’m writing, I can’t edit a different one because my brain is in two different fiction books. This way, I could be dealing with my fiction books at the same time I was writing the non-fiction, or editing the non-fiction, because it’s like two different sides of the brain totally, even though it was writing. One was all fact and information, and one was all just stories.

Yeah, that helps. I can’t do two fiction books at the same time, and I know I could never do two non-fiction books at the same time. But I can do one of each at the same time. I have since learned, obviously.

BAF: Maybe, I got to ask about the photos in the book. There were some beautiful photos. Did you choose a specific photographer?

Sara Dahmen: The photographer that did the majority of the photographs in the book, Christian Watson and his wife, Ellie May, they did the most recent Beekman Boy Cookbook.

He had done some work with Josh and Brent. And I always get those cookbooks because Josh is from the town that I live in. His parents still live here, so I just kind of always feel a connection. And this particular book had such beautiful photos, when I was writing this book, I reached out to Christian and I said, “I’m sure you get inquiries all the time. I just am checking your availability and what you’d cost.” You know, “This is what the book is about. What do you think?”

And he got back, and he’s like, “This is amazing. Let’s make it work. I want to work on this.” And so, he came to Wisconsin. I paid up front, not even having the book sold yet, but I was like, no, I want the right photos for this. So he came to Wisconsin for almost two weeks. We did a couple other quick jaunts. He was out in Portland at the time with his wife, and we did like a weekend out there. We did some stuff. So when HarperCollins, when William Morrow bought the book, I was able to hand them not only a finished manuscript immediately, because I had already written the whole book by the time I had met with them. But I was able to hand them hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of photos, already done, edited, and professionally taken.

Ones that I liked. That I had been able to help create. So, it turned out really cool. Everything was very serendipitous.

BAF: They didn’t impose their vision or thoughts on it.

Sara Dahmen: No everyone at William Morrow was extremely supportive of this book in all the ways and shapes it came. I think the cover photo was kind of the biggest issue. Just what should it be? What should it look like? And that ended up being one of my friends, Nicole Stiles, she showed up, and we shot it in my garage, like on a November morning.

BAF: It’s a great action shot.

Sara Dahmen: It was one of the first ones we took. And then, as the shoot got longer, because they would ask us to do different things from New York. They’d send us messages, because we would send photos, “This is what we got.”

“Can you do this, can you … ” And we would kind of go back and forth, right? And as we were going, they were like, “None of these are really working. Sarah looks kind of worried or nervous. And I’m like, because I’m wearing no welding gloves, and it’s over a fire, and I’m like, it’s getting … I can’t keep doing this. There is a time lapse here where we cannot shoot this anymore. We’re done. Because the pan is hot, and unless you want me fully suited up for the cover photo, which I don’t think you want, we got to stop. So yeah, I’m getting nervous. That pan’s getting hot.

And I had no gloves on.

BAF: Yeah, well it was becoming less organic. The first one just happened.

Sara Dahmen: Yeah.

BAF: I’m curious, do you have a studio or a laboratory somewhere?

Sara Dahmen: No, to do my work, I took over half of our garage. It has now been converted over into a copper shop.

So half of my garage is modern tools, things you would see, you know, grinding wheels and buffing wheels, and rivet guns and air hoses. And the other half is all the vintage tools that I use to build custom work. So those are all the hand rotary tools and stakes from the 17 and 1800’s. And it’s really dirty all the time.

BAF: So, it sounds like you have no garage as such.

Sara Dahmen: No.

BAF: Cars are outside in the Wisconsin cold.

Sara Dahmen: Well, we can fit one in. And if I shove all my tools over in the winter, we can fit the other one in, but it’s really tight. And it’s not fun. And I complain. And so, my husband actually said, he goes, “Fine, let’s talk to some of my garage guys. Maybe we can build you a shop in the backyard.”

And I’m like, “Yes, please, get me out of the garage. The fluctuating temperatures are bothering my tools.”

BAF: It must be kind of cold to work in the winter in Wisconsin in the garage.

Sara Dahmen: Oh, it’s horrible. It is horrible. And that’s one thing, I have to tin in January. And if it’s negative 20, I still have to open the garage doors for ventilation. And it’s not fun. Like after this, I’m going outside and I’m like, “It’s so nice outside. It’s June, and it’s like 70. And it’s so luxurious to be able to tin with all the garage doors open and a tank top on.”

BAF: Sure, yeah. Well, maybe I should ask, what’s next for you? You’ve done this very cool book. Some historical fiction. What’s next?

Sara Dahmen: That’s a good question. I have no idea if I’ll ever write another non-fiction book. There’s been ideas floating around, so maybe. Right now, it hasn’t percolated long enough for me to be able to sit down and write it. I do have a third historical fiction book that should be out … I thought it was going to be fall, but it might actually be spring of 2021. And so, now that that’s with my editor, I’m working on the fourth novel in that series. And it’ll be very timely, because it has to do with understanding disease and germ theory. Funny enough, but it was written five years ago, and I’m editing it now. And I’m working on it, and it’s very timely.

But yeah, it’ll probably be that. I have been doing a lot of screenwriting, and I have gigs. I have a manager in L.A. who hooks me up with gigs to write screenplays, and to work on productions. So I’m sure there’ll be that if things pick up in that part of the industry, in the entertainment industry.

Yeah, I don’t know. You know what’s really bad? If you asked me what my five year plan was, heck, even my three year plan? I wouldn’t be able to tell you. I don’t have one. I don’t have a … I don’t have a two year plan. I just do. Like, I just kind of do. And I know you’re supposed to have these plans, right, so that you have goals and you can work towards them. But I don’t like to do that, because I feel like sometimes you end up saying no, then, to things that you might say yes, that you would have said yes to otherwise, and miss an opportunity that could make your world even better.

So, you know, and my husband totally has this five year plan and the ten year plan, and I’m just like, “It’ll happen, and it’ll be great, because you just say yes to everything and then see what happens, and get your life experiences. And things will just keep going.” I mean, look at this. I have this book out. Look at that, I didn’t plan on that. That was not a goal. Like, a non-fiction book. Just, it happened.

So I don’t … Yeah, it’s not like a really good answer, is it? I’m like, I don’t know, there’ll be stuff happening!

![]()

Booksaboutfood.com©2020

Sara Dahmen’s beautifully photographed book is the most useful resource on copper cookware I’ve come across. . . . Copper, Iron, and Clay is an indispensable cookware reference that every cook should have in their library. I learned so much from it . . . and you will too! – David Lebovitz, author of My Paris Kitchen and Drinking French

Dahmen, a cookware coppersmith, explains the enduring benefits of copper, iron, and clay in this illuminating how-to and recipe manual. . . . This terrific volume is sure to result in a greater respect for kitchen gear among amateur cooks and professionals alike. – Publishers Weekly

Author, coppersmith, and occasional chef Dahmen takes readers on a very personal journey in her discovery of and fascination with copper, iron, and clay. . . . It’s a well-photographed learning adventure peppered with a dozen-plus interviews of artisans, chefs, and manufacturers (e.g., Valerie Gilbert of Mauviel, Giulia Ruffoni of Ruffoni Copper). – Booklist

[Dahmen] describes how she became a coppersmith and started her line of handcrafted products. . . . Along with her passion for historical recreation and her determination to master the physical and technical challenges of the craft. . . . [Her] new book is her way of keeping the practical wisdom she learned from older smiths alive. – Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Leave a Reply