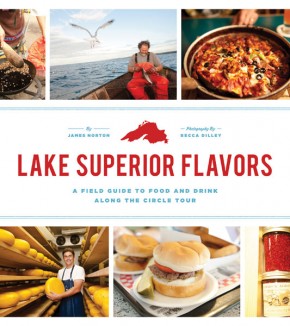

Lake Superior Flavors A Field Guide to Food and Drink along the Circle Tour

Photography by Becca Dilley

Showcasing the wild beauty and rugged authenticity of the places and people along the circle tour, Lake Superior Flavors is ideal for local foodies and for visitors who want to learn about food traditions through delicious eating and lively traveling.

From the founders of the popular food website Heavy Table comes Lake Superior Flavors, a celebration of food culture around the shores of the greatest of the Great Lakes. Author James Norton and photographer Becca Dilley take readers on a culinary tour around Lake Superior, hitting high-traffic tourist spots and cultural institutions as well as off-the-beaten-path discoveries. Norton and Dilley document fine dining, diners, and dives; shop at farmers’ markets; and even try foraging from the land and the lake.

Norton and Dilley also meet food producers and artisans—fishermen, cheesemakers, brewers, and more—and explore the culinary history and current food culture of four distinct regions. Along the North Shore of Minnesota, Norton and Dilley ride with a herring fisherman struggling to preserve his way of life. In Thunder Bay and Ontario, the authors investigate the roots of the locavore movement in a remarkable conversation with an Ojibwe woman about native food. In the remote Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan, the pair encounters a group of philosophical gourmet monks who make jam from foraged berries. And on the south shore of the lake, they talk with a Wisconsin cheesemaker and goatherd who takes his flock on a nightly walk—cocktail in hand. Alongside Norton and Dilley’s travelogues are capsule reviews of restaurants, insightful tasting notes, and sidebars featuring important dishes of each region—from smoked fish and skillet-popped wild rice to pannukakku (Finnish pancakes) and cudighi (Italian meatball sandwiches).

James Norton and Becca Dilley run the Heavy Table website and are the authors of The Master Cheesemakers of Wisconsin. Norton is a regular contributor to the Christian Science Monitor and Minnesota Monthly and makes frequent appearances on Minnesota Public Radio’s The Current station.

Lake Superior is a big lake, as Jim and Becca acknowledge on page one of their book, and the food and culture that it creates, inspires, and nurtures represent some of the best in our country. In this book, the daring duo perfectly captures the essence of who we are in the Upper Midwest, and their prescriptive approach for the traveler is both an alluring siren’s song and one of the best guides of its type. A Baedeker with soul for a new generation.

—Andrew Zimmern

Lake Superior Flavors gives us a tour around the Lake by way of its fare, a fantastic resource for gastronome visitors and local foodies alike.

—Tim Nelson, Principal, Fitger’s Brewhouse Brewery and Grille, Duluth, MN

The big lake clearly has a profound impact on those who live near it, and Norton has created a unique guidebook that encourages visitors to seek our memorable food experiences. These aren’t reviews so much as in-depth explorations of how these places came to be, and how they thrive in a region that is so heavily dependent on tourism.

—Minnpost

As much travel guide as living history, the book shares the best-kept culinary secrets of this gorgeous, rough land and its generous, plain-spoken people. With his Studs Terkel-like eye for a good tale, Norton portrays these characters in memorable detail, while Dilley’s photos render them in living color.

—Star Tribune

Fort William’s Edible History Lesson

audrey deroy and ojibwa food traditions

Audrey DeRoy straddles two worlds through her work as a historical interpreter at the Fort William Historical Park. As Niizho Miigwanag (“Two Feathers”), she is a native heritage specialist bringing the sights and sounds of history to visitors from the present era, and she is an ambassador from the world of the Ojibwa (or Anishinaabe) to largely European-descended guests of the fort.

Built on the site of the North West Company fur-trading fort, which was the scene of an attack by mercenaries hired by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1816, the Fort William complex includes forty-two reconstructed period buildings. “We’re ensconced within a natural environment—there’s far less encroachment of modern life,” says Marty Mascarin, the communication officer at Fort William. “It helps to re-create this period atmosphere and take you back.” The complex stands as a remarkable place of learning and entertainment, a historic tourist attraction that is one of the biggest draws to the Thunder Bay area. Costumed reenactors, playing the roles of nineteenth- century tradesmen, voyageurs, and Ojibwa, mill among the visitors and bring a sense of living history to the fort.

Under the shelter of a reconstructed wigwam, we spoke with DeRoy about historic and contemporary First Nations food practices. “We know for a fact that traditional foods have a lot of really good medicinal properties that have helped us sustain a good diet and way of life, prior to the things being put into us today,” she says. Much of her knowledge of Ojibwa food is presented through the lens of native health and nature lore, a complicated system of “medicines” not dissimilar to the “humors” of the European Middle Ages or the concept of chi in Eastern healing.

“You know about the epidemic of diabetes—that’s huge among our people,” she says. “We love the sweetness from the maple sugar, and we ate that for generations. That was a huge food source. And now today they’re finding out that maple syrup is the preferred sugar for a diabetic—and when you think about that, that’s a sure sign that our diet was better for us. I find a lot of our people are going back to that. That’s the transition from being reliant on grocery stores and urban life.”

The challenge of sticking to a traditional diet—which can be difficult to follow even under the best of circumstances—is intensified by the ready availability of modern fast food, rich in sugar and fat. “If you don’t introduce it to your children when they’re babies, they’ll basically turn their nose up at it, because they’re so addicted to chicken fingers and French fries,” she says. “Instead of frying our foods, we used to bake our foods, and we’re getting back to that, too. Frying foods is terrible for our people . . .it’s terrible for everybody!”

Among First Nations communities such as the Ojibwa, there is an increasing emphasis on moving away from white flours to white rice and corn flours. But not all of the old ways will be easy to return to. “I don’t know if you’ve seen a moose around lately,” she says. “I remember as a young woman we were raised on moose in the fall time, and deer meat in the late fall and winter. And then rabbits . . . still fishing, we still had fish. When spring came, there was lots of fish.”

As we talk with DeRoy about Ojibwa food, it soon becomes clear that her food knowledge alone would be enough to launch a restaurant as chic and hyperlocal as the foraged food–driven Noma in Denmark, named best in the world by Restaurant Magazine from 2010 to 2012.

From smoked blueberries to cattail roots to wild carrots to fruit leather made of birch bark and all manner of exotic game meats, the food folkways she shares seem at once ancient and fully modern, plugged in to the seasons and the environment in the effortless manner that can come only from generations of practice. Imagine a meal of beaver tail and bear meat, served with evergreen teas and wild rice—it sounds dodgy at first but delectable when filtered through knowledge situated in the land and its flora and fauna.

“The fur traders here at Fort William were sustained on fish,” chimes in Mascarin.

“But oh my goodness, have you ever tried beaver, Marty?” asks DeRoy. “We wouldn’t normally get a beaver until wintertime when the coat is nice and thick—and the meat, oh the fat from a beaver in wintertime, it is so delicious. It’s like eating a beef roast.”

As is true with most everything wild and gamey, preparation is everything. “You just need to know how to doctor that beaver up,” she says. “You put the medicines in there, and you know, those medicines will take the gaminess out of the meat. This plant is amazing, it acts like a bay leaf, it gives it flavor. I always say, cook it for a long time over low heat. Beaver, you can eat the tail, too. You just take a Y-shaped branch, and you stick it into the tail, and you roast it by the fire. And when you’re done with it, you take a bite, and it tastes really greasy, but it’s also crunchy, and it tastes really good.”

DeRoy also sang the praises of bear and, first and foremost, its fat—a vital resource for Ojibwa surviving the lake’s long, cold winters. “Have you ever had bear meat? It tastes like pork. I don’t eat it, it’s one of my helpers [sometimes known as “spirit animals”], but it tastes like pork. One good bear in the fall is like fifty pounds of fat. And when you think about that, we always mix fat in with our dried food, like pemmican and that, we mix dried fish with berries.”

Moose, too, was once a staple food of the local peoples of the lake. We’d heard from numerous people that moose is pretty close to inedible, but DeRoy had knowledge to share: “I know people say [about moose], oh, it tastes so lousy, and I’m thinking: ‘How do they cook their food?’ I know watching my mom and my aunties and my uncles—the best thing with moose is first you have to hang and drain the blood out of it. If you don’t do that, the moose meat will taste funny. The next thing is when you’ve harvested the moose, it tastes very good in the fall time because they have all the nutritious things they’ve been eating in the summertime. And the thing with moose meat—you have to simmer it.

“You cook it in a little bit of its juices, and a little bit of water, and you can add a bay leaf, you can use maple sugar to sweeten it a little bit, you could use wild ginger. . . all kinds of things. You start adding things to it—onions, and carrots, and celery, and things we get in the grocery stores.

“Have you ever had moose tongue? Moose nose? Oh my goodness. The nose you have to burn all the hair off, then you just roast it. It’s really, really good. The tongue. . . have you ever had liver p.t.? It tastes like that! It looks kind of weird sitting in the fridge, all cooked up. But it’s really good.” She attests to the meat’s nutritional value as well: “People used to say moose meat has no nutritional value, but I was raised on this meat, how did I get so healthy? That’s not true! When you look at all the good medicine those animals are eating, you’re eating that medicine, too.”

Beverages weren’t neglected in Ojibwa cuisine, either. “All the berries are turned into drinks,” she says. “We don’t even drink water—it’s usually mixed with maple syrup and berry juice. It’s really, really good. Most of our drinks are teas. A long time ago, our people would have tea parties.” “Tea” in this case means a local tisane (or herbal tea) from a plant in the heath family. “The Europeans call it Labrador tea, and it grows in swampy areas around here—our people call it muskeg or swamp tea,” says DeRoy. “It’s really good for you. It gives you a lot of energy, and it gives you a good feeling inside if you have a cup or two a day. You don’t want to have any more than that.”

You can also make teas from the green (“not rusted”) leaves of strawberry plants, DeRoy says. “You dry them, and then you boil your water and put the dried leaves in. You have to use a certain amount, you can’t put in a whole pile or it becomes very, very strong. You could have a strawberry drink with the strawberries watered down and a little maple syrup in there.”

As DeRoy tells it, food is more than fuel—it’s the web that holds a community together. Key to that relationship are local fish. “We love our pickerel,” she says. “We love our sturgeon. And some people prefer to have northern pike. Suckers, white suckers, are really good smoked. A lot of our people really love white sucker when it’s smoked. I love frying mine with ground-up cornflakes—oh my goodness, pickerel is one of my favorites.”

But the true key to enjoying fish, says DeRoy, is sharing it with the community. “Some people purchase it because they don’t have any means to go out on the water,” she says. “Some people fish and gill net. That’s how I get my pickerel, I go out gill net ting with my partner. We don’t keep it for ourselves, too, that’s called a stingy box, you know, the freezer.

“You want to hand out the food. When we get a net full of fish, we share it. We share it with all the elders that we know who can’t get that kind of food, the traditional food.”

Leave a Reply