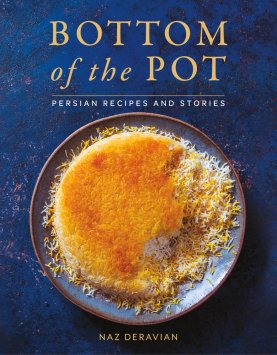

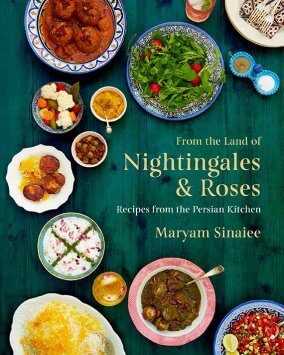

From a Persian KitchenFresh Discoveries in Iranian Cooking

The variety of beautiful, jewelled rice dishes, hearty winter dishes and crisp summer salads showcases the diversity of Iranian regional cooking, from the sweet and sour flavours of the northern Caspian coast to the spicy and aromatic tastes of the south and the Persian Gulf.

The food of Iran is a riot of tastes and aromas, and is one of the great – but least known – cuisines of the world. With an emphasis on the use of seasonal ingredients, fresh herbs and fragrant spices, Jila Dana-Haeri here presents a unique guide to quintessential Persian cooking. The variety of beautiful, jewelled rice dishes, hearty winter dishes and crisp summer salads showcases the diversity of Iranian regional cooking, from the sweet and sour flavours of the northern Caspian coast to the spicy and aromatic tastes of the south and the Persian Gulf. The complementary mix of flavours – from the fresh tartness of pomegranate seeds to the subtle perfume of saffron, tarragon, dill and fenugreek – makes for an array of mouth-watering recipes that are now, thanks to Dana-Haeri’s contribution, accessible to cooks of all levels. Sumptuous meat dishes are offset by accents of berry, walnut, coriander and mint to create recipes that are simple to make but bold in flavour. Balancing meat, fish, vegetables, fruit, herbs and spices, this book provides a delicious journey through the truly original tastes of Persia.

This beautifully illustrated cookbook offers an enticing selection of recipes for any occasion, be it a quick supper, lavish dinner party, summer picnic or winter feast. Featuring stunning photography and introductions to Iranian cuisine and culture, From a Persian Kitchen will be essential for all interested in expanding their cultural and culinary horizons.

Jila Dana-Haeri is an expert in Persian cuisine. A medical doctor with a specialty in clinical pharmacology, she has a particular interest in nutrition, which is reflected in her recipes. Jila grew up in Iran where she honed cooking skills in her family kitchen, and now lives in the English countryside where she entertains family and friends with her Persian dishes. She is the co-author of New Persian Cooking (I.B.Tauris, 2011).

Dill and Yogurt Soup

Aash-e maast

Serves 6–8

Preparation about 20 minutes

Cooking about 2 hours

This is a very smooth, aromatic and creamy soup. My friends refer to it as ‘Jila’s aash’. It has become the staple of our parties and festivities.

My recipe is different from the traditional one inasmuch as dill is the main herb used, rather than the customary mix of parsley, coriander, chives and spinach. This is an easy aash to prepare and can be made all year round, replacing fresh dill with the dried version if necessary.

INGREDIENTS

200 g/7 oz split peas

150 g/5 oz rice

120 g/4 oz dill (or 4 tablespoons dried dill)

1 medium-sized onion

2. litres/4 pints chicken or vegetable stock

1 teaspoon turmeric

450 g/1 lb Greek-style yogurt

5 tablespoons lemon juice

30 g/1 oz butter

4 tablespoons vegetable oil

salt and pepper

GARNISH

1 large onion

1 tablespoon dried mint

3 cloves of garlic, finely chopped

4 tablespoons vegetable oil

Preparation

Wash the split peas in cold water, add boiling water and let them soak for at least a couple of hours. Wash the rice repeatedly in cold, salted water and soak.

If using fresh dill, wash it and dry in a salad crisper. Pinch off the leaves and tender stalks and discard the thicker, tougher ones. Pile the leaves on a chopping board and chop them finely with a sharp wide-bladed knife.

Peel and finely chop the onion.

Cooking

In a large heavy-based saucepan melt the butter; add the oil and heat up. Fry the chopped onion until soft and golden. Drain the split peas and add to the pan with the turmeric. Stir a couple of times and then pour in about half of the chicken or vegetable (for the vegetarian option) stock. Bring to the boil. Put the lid on and reduce the heat. Allow to simmer until the split peas are completely cooked (approximately 1 hour). No salt should be added at this stage. Once the split peas are cooked, drain the rice and add to the saucepan. Add the rest of the stock and allow to simmer for a further half an hour. Stir occasionally to stop the mixture from sticking to the bottom of the pan. When the rice is almost so soft that you cannot distinguish the grains, add the finely chopped fresh (or dried) dill. The mixture should be creamy and thick at this stage. Add small amounts of boiling water to adjust the consistency if needed (more water will make the soup thinner). Allow to simmer for 30 minutes on a low heat, stirring occasionally. Then remove from the heat and allow to stand for five minutes. Mix the lemon juice with the yogurt and add to the pan, stirring all the while to mix thoroughly. Taste and adjust the seasoning as necessary. Keep warm; the aash is served hot.

GARNISH

Fry the onion in 2 tablespoons of oil until light brown. Add the chopped garlic, stir and put to one side. In another small frying pan, heat up the rest of the oil. Add the dried mint. Stir and remove from the heat immediately. Serve the aash in a soup bowl and decorate with both garnishes.

Aash

Aashes are rich, nutritious soups with a thick consistency similar to porridge. The importance of aash in Persian cuisine is such that in Farsi a cook is called aashpaz, meaning ‘the one who knows how to make aash’!

Aashes are cooked all over the country, each region having its own favourite. For example, in the north the aashes are rich with herbs and fruits and the dominant taste is sweet-and-sour; in the south they tend to use fewer herbs and the aashes are more sour than sweet. The difference between aashes in the two regions is best illustrated by pahti, beetroot and pulse soup, which in the south is hot and spicy with the addition of tamarind juice and coriander, whilst in the north they make it with pomegranate syrup, without coriander and chilli (see p. 27 for the southern version).

Khoresh

Khoresh or khoresht is a rich sauce, almost always served with plain rice. The nearest equivalent in the West is stew or casserole, although these would probably contain more meat than a traditional khoresh. Khoresh can be made with meat or fish and be combined with vegetables, herbs, fruits or pulses.

Since meat is the most expensive ingredient in a meal, the quantity required would be less when mixed with pulses, herbs or vegetables. A further benefit of such a combination is a healthier diet, with the addition of vitamins, minerals and other proteins to the meat dish.

The diversity of sweet-and-sour, aromatic and spicy, also applies to khoreshes. A typical example of a sweet-and-sour khoresh is naaz khatoon, lamb with herbs and aubergine in a sweet-and-sour sauce, which originated in the north (p. 57). An example of a dish that originated in the south is a khoresh from Bushehr, featuring spicy coriander: aaloo gashneez (p. 77). The dominant herbs in naaz khatoon are parsley and mint, in contrast to the coriander of the southern-origin khoresh.

Historically, in the provinces by the Caspian Sea in the north, khoreshes with fruits like quince, apple and prune and vegetables like rhubarb were very popular. In the south, potato and tomato and vegetables like okra were the dominant ingredients. Again, the seasoning in the north was predominantly citrus juice or pomegranate syrup. In the

south, tamarind juice was the preferred choice.

Rice

Rice is the hallmark of Persian cuisine. Great attention is paid to the preparation and presentation of rice dishes. It is important for the rice grains to be fully elongated (qad

keshideh) and separate. A dish of rice should be aesthetically pleasing as well as exciting the appetite with its aroma. Just as it is important for the rice grains to be perfectly cooked through without any stickiness, it is also important for the other ingredients mixed in with the rice to be cooked but remain whole and recognisable. The beauty of morassa polo (jewelled rice, p. 143), for example, is in the juxtaposition of the bright ruby-coloured barberry with the green pistachio, orange and carrot juliennes scattered in the saffron rice.Even plain rice is decorated with saffron to lend it morevisual interest.

There are also sticky rice dishes called dami or dampokht, which are usually cooked for informal occasions. These started life in the north, as rice is grown in the provinces by the Caspian Sea and has long been the staple food of these regions. However, a spicy and aromatic version of lakh lakh (sticky rice with fish, p. 162) is a ‘poor man’s dish’ which was taught to me in my southern home.

The diversity of rice dishes is illustrated by kalam polo (cabbage rice, p. 141). The version I learnt in my northern home, for example, contains sultanas, which gives it a tinge of sweetness; however, the dish I learnt to make in the south (kalam polo Shirazi; see the recipe in New Persian Cooking) contains dill and other aromatic herbs and is not sweet.

The centrality of herbs in Persian cuisine

Herbs play an integral role in Persian cooking. The amounts used often seem incredible to non-Iranians. Herbs serve as the building blocks of most dishes and are used in abundance: they are added to rice, constitute the main ingredient of khoreshes, and are the principal component of the stuffing mixes for khoraks. They are also eaten raw as an

accompaniment to most meals.

In the Persian kitchen one encounters a mountain of herbs. As Margaret Shaida describes in The Legendary Cuisine of Persia, herbs are sold in kilograms rather than as a few sprigs. As she so beautifully puts it, ‘The way Persians utilise herbs is not for the faint hearted!’ This is especially true when the time comes to chop them, often finely, as is

the requirement for most herb dishes.

In Iran, herbs are bought daily, having been freshly picked and brought to the shaded markets and kept cool by sprinkling water. I still remember the herb market in Bushehr, on the Persian Gulf, where stand after stand sold coriander, parsley, mint, basil, chives, tarragon, and many more, each made into large bundles and arranged in hessian baskets. The market felt fresh with the scent of mint mixed with basil, and cool in the heat of a summer morning.

Leave a Reply