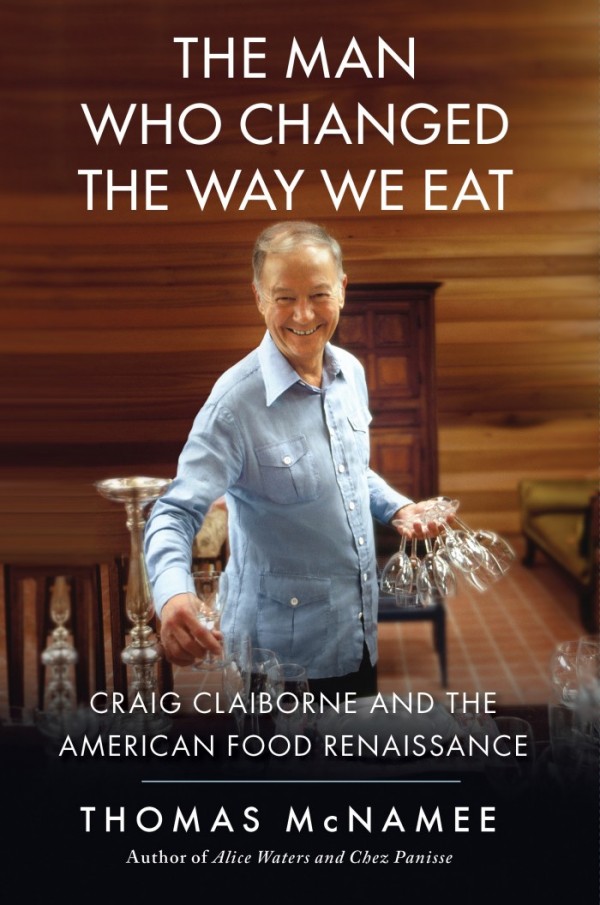

The Man Who Changed the Way We EatCraig Claiborne and the American Food Renaissance

In the 1950s, America was a land of overdone roast beef and canned green beans—a gastronomic wasteland. Most restaurants relied on frozen, second-rate ingredients and served bogus “Continental” cuisine. Authentic French, Italian, and Chinese foods were virtually unknown. There was no such thing as food criticism at the time, and no such thing as a restaurant critic. Cooking at home wasn’t thought of as a source of pleasure. Guests didn’t chat around the kitchen. Professional equipment and cookware were used only in restaurants. One man changed all that.

In the 1950s, America was a land of overdone roast beef and canned green beans—a gastronomic wasteland. Most restaurants relied on frozen, second-rate ingredients and served bogus “Continental” cuisine. Authentic French, Italian, and Chinese foods were virtually unknown. There was no such thing as food criticism at the time, and no such thing as a restaurant critic. Cooking at home wasn’t thought of as a source of pleasure. Guests didn’t chat around the kitchen. Professional equipment and cookware were used only in restaurants. One man changed all that.

From the bestselling author of Alice Waters and Chez Panisse comes the first biography of the passionate gastronome and troubled genius who became the most powerful force in the history of American food—the founding father of the American food revolution. From his first day in 1957 as the food editor of the New York Times, Craig Claiborne was going to take his readers where they had never been before. Claiborne extolled the pleasures of exotic cuisines from all around the world, and with his inspiration, restaurants of every ethnicity blossomed. So many things we take for granted now were introduced to us by Craig Claiborne—crème fraîche, arugula, balsamic vinegar, the Cuisinart, chef’s knives, even the salad spinner.

He would give Julia Child her first major book review. He brought Paul Bocuse, the Troisgros brothers, Paul Prudhomme, and Jacques Pépin to national acclaim. His $4,000 dinner for two in Paris was a front-page story in the Times and scandalized the world. And while he defended the true French nouvelle cuisine against bastardization, he also reveled in a well-made stew or a good hot dog. He made home cooks into stars—Marcella Hazan, Madhur Jaffrey, Diana Kennedy, and many others. And Craig Claiborne made dinner an event—whether dining out, delighting your friends, or simply cooking for your family. His own dinner parties were legendary.

Craig Claiborne was the perfect Mississippi gentleman, but his inner life was one of conflict and self-doubt. Constrained by his position to mask his sexuality, he was imprisoned in solitude, never able to find a stable and lasting love. Through Thomas McNamee’s painstaking research and eloquent storytelling, The Man Who Changed the Way We Eat unfolds a history that is largely unknown and also tells the full, deep story of a great man who until now has never been truly known at all.

Thomas McNamee is the author of Alice Waters and Chez Panisse. His writing has been published in The New Yorker, Life, The New York Times, and The Washington Post. He lives in San Francisco.

Website: http://tomfoodery.blogspot.com/

In his day Craig Claiborne was the most influential person in the American Culinary landscape. It is an influence that has contiued to this day. He became the food editor of the New York Times in 1957. His restaurant reviews in the Friday edition of the paper were highly anticipated and held the weight to close a restaurant. Claiborne was more that a reviewer. In many ways he created food journalism. He championed the likes of Julia Child and Marcela Hazan. He learned and wrote about ethnic food for the general public. He searched for new ingredients. The food ‘scene today has been shaped in large part due to the work and legacy of Craig Claiborne.

Yet for all is accomplishments and contributions Claiborne is a fading culinary figure.

Writer Thomas McNamee (Alice Waters and Chez Panisse) like so many New Yorkers of the day followed Claiborne’s reviews. He learned to cook from Claiborne’s books and followed his lead on new ingredients. Now he has written the definitive biography of the man.

Thomas McNamee recently talked to Boooksaboutfood.com about his book The Man Who Changed The Way We Eat.

BAF: His influence is something of which I don’t know if we’ll see again.

T. McNamee: I think it’s impossible now because the food world was so much smaller then. There was no food world. He created the food world. There just weren’t very many Americans interested in food until Craig Claiborne created the interest and he created this empire of fascination with food. He was the single authority on it. James Beard tried to be, but James Beard was so corrupt that his authority was doubtful because he was for sale. Then there were wonderful writers like M.F.K. Fisher, but she was so specialized and that she necessarily had a small audience and she never had a platform like the New York Times.

Craig was in a position of having built the mountain that he was on top of. As his career advanced and the food world bigger and bigger and bigger and he introduced new leaders. He would discover for example, Marcella Hazan who was just a housewife until Craig Claiborne lifted her to fame as it were and Julia Child, he introduced Julia Child to the world. There came to be duchies you might say within his kingdom and as time passed, there were worlds within worlds of the food world. Of course, there were many leaders and no single leader and of course, as we see today there’s infinite numbers of worlds of food and certainly no single leader.

BAF: It was almost a one-man show.

T. McNamee: That’s right. As a food editor of the New York Times he was the entire food staff of the New York Times, except that there were people there in the test kitchen who tested recipes, but there was no other food writer. In fact, for a long time there was no other honest to God restaurant critic in the United States. He invented the job. There were the so-called restaurant writers and other newspapers who would go and get free meals from restaurants, they wrote up what were pretend, make-believe the views which were invariably positive because they were basically written to keep that restaurant’s advertising in Kansas City Star or whatever paper it happened to be. It wasn’t really a review. It was just an advertorial.

Craig introduced honesty and critical rigor to restaurant reviewing in the same way that the other critics of the Times would review movies or art or theater, books. The Times paid for his meals. He went anonymously and he judged the restaurants according to his rather carefully and strictly defined criteria and that had never been done before. He was something of an intellectual and he wanted food criticism to be respected at the same level as criticism of the other arts. He thought that food deserved to be considered as difficult and as expressive and as rich a medium say as painting or writing.

BAF: What was your knowledge of Craig Claiborne before going into this?

T. McNamee: When I graduated from college, I didn’t know anything about cooking. I got married very young, I was 22 and my wife, who was my high school sweetheart, was 20. She graduated from college in three years so that we could get married and she didn’t know anything about cooking either, but her mother was a good cook, which my mother was not. We decided to learn to cook together and we had Julia Child Volume 1 and we had Craig Claiborne’s New York Times Cookbook. That was our Bible

BAF: You were living in New York at the time?

T. McNamee: I had moved to New York directly after college…We became followers of Craig Claiborne. When his restaurants reviews came out, we would run out and buy the Times early in the morning and that was the first thing we would turn to. The way a Yankees fan would turn to a ball game coverage. We were acolytes of Claiborne’s from way back from the time I was 22.

BAF: As a boy to get away from his parents, he would go in the kitchen and stay with the cooks?

T. McNamee: He was what they called a sissy in Mississippi. From the time he was a little boy, he was soft and pink and somewhat effeminate. In Mississippi, that made you bait for all the bully boys of the neighborhood. He was tortured not only by his peers, but also by the big macho teachers at his school who would just pick on a child like that. He had virtually no friends and no shelter. His father was a depressive and withdrawn character who had lost a bunch of money the same year Craig was born, 1920 and was no help at all. His mother was this brittle would be gentlewoman who was filled with this gushing, overflowing with affection for Craig.

The only place he found emotional comfort as a child was in the kitchen of his mother’s boardinghouse because his father was broke. His mother had to do something to keep the family alive and that was to run a boardinghouse. The kitchen staff as would be inevitable in those days were all black people, working for peanuts, all really good cooks because Craig’s mother despite her other flaws was an extremely good cook. She didn’t have to get her hands dirty to do it. She just taught it to the kitchen staff. Craig grew up with the aromas and the sounds of old-fashioned Southern cooking and the kitchen staff were beautiful to him. They took him in and that’s where he found emotional solace and undoubtedly, that was the imprinting of food that sustained him and moved him toward everything else that he did with his life.

BAF: He used the G.I. Bill to go to Switzerland to study cooking?

T. McNamee: That’s right. He messed around for a long, long time, not knowing what he was going to do with his life. He was in the Navy in World War II and then he floated around Chicago until Korea started, he went back in the Navy, and was finally in his last year in Korea that he realized that he wanted to do something having to do with food. He wanted to write about food. He had gone to Journalism School at the University of Missouri so you wanted to be a writer of some sort.

He finally decided he wanted to write about food and that’s when he decided he wanted to go to the greatest hotel school in the world which at that time he thought was going to be the Cordon Bleu in Paris. His mother intervened and found out from this French headwaiter at the Peabody Hotel in Memphis that there was a better school which was the great hotel school in Lausanne, Switzerland. He told Craig about it and he applied there.

BAF: Do you think Claiborne, was he aware of what he had accomplished or what he had done?

T. McNamee: I think so. He had a pretty high opinion of himself. He came to be disillusioned with the power he had. He was such a nice man in some ways. He didn’t like having the power to destroy a restaurant because a negative review from Craig Claiborne would do that. It was just like in the old days when a Broadway show got a bad review from the Times, it was over. It closed. That was pretty much the case with a bad review from Craig, at least for a high end restaurant where they put hundreds of thousands of dollars into the restaurant and everything depended on Craig’s review. It was very uncomfortable for him and that’s why he got out of restaurant reviewing part way through his career.

BAF: In your research, was there anything that particularly you came across that really surprised you about him?

T. McNamee: There’s a great many things.

As I biographer, you want to find out about your subjects and their life. Sometimes it’s easy and sometimes is not and in Craig’s case it was definitely not, but eventually I was able to do so. The deeper I got, the deeper I dug, the more interesting he became because he was so conflicted about himself in many ways.

He was angry at himself, disappointed in himself, and yet at the same time he got a lot of fun and deep enjoyment from the world. Discovering how he clicked, was a big piece of what I was doing and not just documenting what he did, what he accomplished, introducing the Cuisine Art or arugula or all the wonderful things he did in the world of food. That was easily enough done. That’s all documented in his published work, but finding out who he was as a person was the fun part for me.

BAF: To actually sit down and have to write about him was that hard to put all the pieces together?

T. McNamee: No. Once I had a sense of the fullness of him and containing all the contradiction and complexity and I had a structure simply of chronological starts. I started with a introduction to who he became and I just start back in his childhood and go straight on through. The information was there. My sense of who he was was there and it went along pretty steadily.

BAF: What are you working on now?

T. McNamee: I’m returning to writing natural history. I’m extracting a story from a book I published in 1997 called “The Return of the Wolf to Yellowstone.” I’m taking a piece of that book and rewriting it and turning it into a book for young adults. It’s been not quite 20 years since the wolves were re-introduced to Yellowstone and they’re doing magnificently well. Yet, there’s still a tremendous amount of controversy about them.

Booksaboutfood.com © 2013

“Craig Claiborne was the greatest influence of my professional life in America. Knowledgeable, dedicated, and driven, he was determined to better American eating habits. As Thomas McNamee nicely portrays in The Man Who Changed the Way We Eat, Claiborne’s impact on the culinary revolution of the last forty years cannot be ignored or overstated.”

Jacques Pépin

“Thomas McNamee’s intensive research, his determined digging in the archives and memories of the major players, brings back the joy, the triumphs, the Hamptons bacchanals of Craig Claiborne–the man who invented professional restaurant criticism.”

Gael Greene, author of Insatiable: Tales from a Life of Delicious Excess

“The Man Who Changed the Way We Eat assures that a poignant life whose meaning so impacted the restaurant world will not be permitted to fade from our collective memories. Bravo Thomas McNamee for illuminating the erudite gentleman who paved the way for today’s legion of professional restaurant reviewers, as well as for an entire generation of amateur critics who now daily express their judgments on every platform the Internet provides. This must-read book profiles Claiborne’s turbulent, brilliant, and unscripted life – which had such a profound and enduring impaction a huge swath of American culture.”

Danny Meyer, author of Setting the Table: The Transforming Power of Hospitality in Business

The fact that he could make or break a restaurant made him uneasy, but it was a fact, and his readers found something thrilling in the danger he threatened and equally in the prospect of discovery. Not a few would rush out to buy the Friday paper and turn first to Craig’s latest review.

The clear result of his critical rigor was a continuous increase in the quality of New York’s restaurants and in others across the country. Long past was the day when a serious restaurant in New York might dare to substitute specks of black olive in place of truffles. “Great cuisine in the French tradition and elegant table service”—Craig’s words in the piece that made him famous—had not “passed from the American scene.” The featureless desert that Craig had predicted forty years before his death was precisely what the American gastronomic landscape was not, least of all in Craig’s adopted home town—in good measure thanks to him. Menus were not “as stereotyped as those of a hamburger haven.” Far from it: By the time Craig left the Times, New York was teeming with restaurants as various as the city’s clans, cults, allegiances, and heritages. From the Bronx to the Battery were Chinese restaurants galore, many of them specializing in regional traditions, including the fiery Sichuanese that Craig had done so much to popularize. Virtually every corner of Italy was represented. Japanese cuisine of high refinement was easily had. There were Brazilian, Vietnamese, Cuban-Chinese, Swiss, Swedish, and Syrian restaurants. No longer were Greek, Indian, and Mexican food served only in cheap joints: Luxurious iterations of each were thriving. With its modernist design and restrained, unaffectedly elegant food, The Four Seasons had redefined formal American dining. New York’s breathtakingly rude French restaurants had had to learn to be polite. Particularly since the opening of Danny Meyer’s Union Square Café in 1985, no new restaurant could hope to succeed without genuine, open-hearted hospitality.

In Craig Claiborne’s columns Diana Kennedy had shown that Mexican food was infinitely more various and complex than the taco-enchilada-refried-bean routine that was all that most Norteamericanos had known of it. Paul Prudhomme had made the previously all but unknown Cajun repertoire familiar. Edna Lewis’s Southern cooking had inspired countless Yankees. The Troisgros brothers’ nouvelle cuisine was now accessible to ambitious American home cooks (though still not easy). Wolfgang Puck’s unique hybridization of French, Italian, and Oriental techniques no longer seemed strange. When Craig left the scene, Pierre Franey was publishing his own cookbooks and soon would have his own TV series. Julia Child, of course, was still charming millions on hers, and Jacques Pépin, having published at least half a dozen books of his own, would soon be co-starring with Julia. Ed Giobbi had introduced Craig to the dandelion’s deep-red Italian cousin radicchio, and now he was winding up work on a cookbook, too, Pleasures of the Good Earth.

Basil, pine nuts—hence pesto genovese. Arugula, balsamic vinegar. Prosciutto di Parma. Crème fraîche, nuoc mam, epazote. Cilantro. Porcini. Macadamia nuts. The Cuisinart. The salad spinner, for heaven’s sake. Almost nobody had ever heard of any of these till Craig wrote about them. As for the recipes, he introduced literally thousands to his readers. He had set new standards of clarity and precision in cookbook writing, and for diversity no cookbook writer had ever come near the range of his work. To this day The New York Times Cook Book of 1961 remains one of the two or three standard reference works that belong in every home cook’s kitchen, and it has never stopped selling strongly.

When new gastronomic possibilities arose, it was Craig Claiborne—and for many years he virtually alone—who brought them before the American public. Here too he was in the position of arbiter. When the nouvelle cuisine was electrifying France, for example, and soon was invading the United States in grotesquely distorted form, Craig took on the task of defining and explaining the real thing and attempting to make something resembling it practicable for Americans. The task of discrimination and education that he undertook was particularly difficult because there was so much nonsense flying around at the time, but that was what you knew you could count on him for. You could trust Craig Claiborne. He made cooking daring, an exploration, sometimes rather daunting, but he convinced you that the adventure would be nothing to fear.

If he could plunge into the street markets of Marrakesh, Marseille, and Oaxaca, why not you? When he wrote that the great three-star chefs of France loved nothing better than to be asked in advance to cook what they wished for a naïve young couple who had never before dined in such style, young couples wrote those letters and dined in bliss, coddled by charming waiters, delighted by little extra courses run out steaming from the kitchen by the chef himself. Craig expressed his own pleasure and ease so gently that in situations where uncertainty and trepidation might have been natural to a newcomer, his readers’ anxieties floated away.

Craig’s legacy has been changing ceaselessly, becoming less recognizably his. The roast canard Bigarade that he mastered at Lausanne may have given way to a rare magret with a quick Grand Marnier déglaçage, which in turn may have given up its place to an artful composition of mosaic, julienne, and bright squiggles, and that dish, now, in Spain, perhaps, or Chicago, may have sublimated to an abstraction, its components deconstructed to smoke, vapor, foam, gel, and a puzzle for the palate—was that a waft of burnt-orange scent, is this fast-melting gelée a decoction of duck? But at each stage of this pell-mell evolution we’ve been paying close attention. It’s second nature for us now to want to know what the critics are saying—certainly the Times’s or our local paper’s but also the grim invisibles of the Michelin and possibly Yelp as well. Quite a few of us even want to know how the dish is made, though we’re as unlikely to try it ourselves as Craig’s readers were to make an attempt at his absurdist turkey galantine of 1961.

Our world is full of restaurant critics; we’re all restaurant critics. Our world is full of chefs; we’re all chefs. Neither of those developments was imaginable before Craig set it in motion.

He probably would find it all a bit amusing now. It’s easy to hear him saying: “I really had no í-dea this would get so damned big.”

—–

EXCERPT FROM THE MAN WHO CHANGED THE WAY WE EAT: CRAIG CLAIBORNE AND THE AMERICAN FOOD RENAISSANCE, BY THOMAS McNAMEE— by permission of the author

Leave a Reply