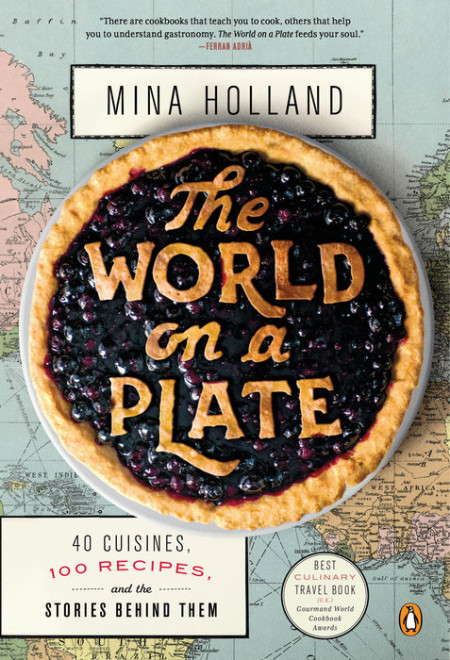

The World on a Plate40 Cuisines, 100 Recipes, and the Stories Behind Them

Eat your way around the world without leaving your home in this mouthwatering cultural history of 100 classic dishes.

Best Culinary Travel Book (U.K.), Gourmand World Cookbook Awards

Finalist for the Fortnum & Mason Food Book Award

“When we eat, we travel.” So begins this irresistible tour of the cuisines of the world, revealing what people eat and why in forty cultures. What’s the origin of kimchi in Korea? Why do we associate Argentina with steak? Why do people in Marseille eat bouillabaisse? What spices make a dish taste North African versus North Indian? What is the story behind the curries of India? And how do you know whether to drink a wine from Bourdeaux or one from Burgundy?

Bubbling over with anecdotes, trivia, and lore—from the role of a priest in the genesis of Camembert to the Mayan origins of the word chocolate—The World on a Plate serves up a delicious mélange of recipes, history, and culinary wisdom to be savored by food lovers and armchair travelers alike.

Mina Holland is the editor of Guardian Cook. She lives in London.

“There are cookbooks that teach you to cook, others that help you to understand gastronomy. The World on a Plate feeds your soul.” —Ferran Adrià

“Fantastic stories about a broad range of cuisines . . . Engaging and illuminating, and the food cries out to be cooked.” —Yotam Ottolenghi, author of Plenty and Jerusalem

“Not only a delight to read but also peppered with delicious recipes, facts and flavors from around the world.” —Rachel Khoo, author of The Little Paris

Zucchini Cream

This almost embarrassingly easy soup, the recipe for which comes from my friend Javi, can be whipped up quickly as a starter before supper, or makes a good hearty lunch year-round. use manchego cheese if you want to be authentic, though cheddar also works perfectly well.

SERVES 4 AS STARTER OR 2 AS A MAIN WITH BREAD

2 large zucchini (about 11⁄8 lb), sliced thickly

1 leek, cut into chunks

1 large potato, peeled and cut into chunks

2 oz hard cheese, chopped or grated (about ½ cup)

11⁄3 tbsp butter

2⁄3 cup milk

extra virgin olive oil salt to taste

1 • Place the zucchini, leek and potato in a large pan and just cover them with water. Be careful not to add too much—2 cups should do it. Bring to a simmer over medium heat and cook for 20–25 minutes, until the potatoes are tender.

2 • Remove from the heat and while the mixture is still hot, add the cheese, butter, milk and a large tablespoon of extra virgin olive oil. Blend to a creamy consistency and season with salt to taste before serving right away.

From The World on a Plate by Mina Holland, published on May 26, 2015 by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright by Mina Holland, 2015.

Central Spain

As you leave Madrid on the train, a graying crinoline of the city suburb blends into a vast stretch of farmland on the horizon, where little happens save for the wind grazing the crops. Life is simple across most of Spain’s Meseta (plateau), belying the sense of license you find in Madrid—where the political pulse and hedonistic heartbeat of Spain beat strongest.

Countless writers have evoked the big-skied bleakness of this countryside—stiflingly hot in summer, biting cold in winter—not to mention films like Bigas Luna’s Jamón Jamón, in which a 1990s-washed Penélope Cruz is but a dot on the massive, dry, rolling horizon. the odd wooden bull—giant, painted black—crowns the occasional hill and reminds you of your Spanish whereabouts as the nondescript yellow landscape flashes past.

Central Spanish cuisine is noticeably less varied than elsewhere in the country. Seized from the Moors in 1492, this is a vast area that was governed by a small elite until relatively recently, limiting the scope of different foods available to the majority of people. Meat has traditionally been a luxury. Carnivorous delicacies include cochinillo (suckling pig), game (squab, quail, partridge, rabbit and wild boar, which sometimes congregate in a stew to be eaten alongside local flatbread made with chickpea flour) or baby lamb. Nevertheless, some of the products that most define Spanish flavors, such as pimentón and saffron, have their origins in central Spain. It is also a cuisine in which the lingering influence of the Moors and the Jews is clearly visible.

Though it is the largest city in Spain, Madrid is a small, compact place. The population of its metropolitan area (about 6.5 million) is roughly double that of the city center, which you can walk across in half an hour. In 2009, I lived just north of Fuencarral by Bilbao metro station, which I was virtually able to ignore, preferring to walk down through the bohemian nook of Malasaña to reach the center. My route took me along busy Gran Via, past the sad faces of girls waiting for business on Calle Montera, and the throbbing Plaza del Sol, where people protest and visitors flock. Beyond that: Plaza Santa ana, where street artists woo tourists; the big galleries of huertas; ever-sunny Retiro park and La Latina, where on Sunday the city’s tapas culture comes out in full swing.

Small in size but endowed with a sense of endless possibility (I was frustrated only by an inability to find good hummus and my bra size), Madrid is a special place. Even amidst the din of noisy Spaniards and tourists, of boozy nights and traffic, you can find peace. And although I ended up making my own hummus (no hardship, really), Madrid boasts some of the best food in Spain. There is a huge appetite for Spanish regional cuisines, which is reflected on a Sunday amble down Calle de Cava Baja in La Latina. this little street becomes (unofficially) pedestrianized on a Sunday afternoon, when the tourists and locals alike hop between bars specializing in anything from Canarian to Galician and andalucían to Catalan cuisines.

You might expect that being so far inland would compromise the quality of its seafood. But the capital arguably has the best fish market in all of Spain, Mercado de San Miguel, where old faithfuls like gambas (prawns) and trucha (trout) convene with the more regional specialties like percebes (goose barnacles) and pulpo (octopus) of Galicia.

For all the great food that assembles there, however, Madrid doesn’t have a lot to call its own. Cocido Madrileño is the exception: a slow-cooked stew using chickpeas, potatoes, several types of meat and sausage including chorizo, morcilla (blood sausage), pork leg, beef brisket, jamón serrano and sometimes chicken. The dish is said to have originated with the Spanish Sephardic Jews and bears similarities to adafina, a slow-cooked stew for the Jewish Sabbath.*

Jewish influences are everywhere in central and southern Spanish cuisine— from the use of chickpeas and eggplants to generous lashings of garlic and almonds, or honey in desserts. the food native to Madrid is similar to that found out on the Meseta: stews made with pulses and offcuts of meat, bread, Manchego sheep’s cheese and jamón. Dishes from central Spain are guaranteed to please the lover of one-pot dishes: rustic flavors congregate in simple, warming cocidos or soups (as in Portugal, see page 76). If you understand the fundamental base ingredients—pimentón, garlic and salt—then these dishes are easy to replicate at home, or can simply be used as inspiration for meals cooked in a Spanish style.

Claudia Roden aptly subtitles her chapter on central Spain with “bread and chickpeas”—two foodstuffs eaten across central Spanish society, from peasants to princes. the Meseta, with its light, dry soil and long hot summers, is suited to the growth of grains like wheat and barley and pulses like chickpeas (garbanzos) and lentils (lentejas). Chickpeas are a good canvas for other flavors: chorizo or offcuts of meat, pimentón in soups and cocidos. These are cheap, nutritious and perennially sustaining complete meals.*

Migas, bread crumbs sautéed in olive oil, make a simple but filling accompaniment to all sorts of food and can be seasoned with chorizo, bacon, garlic, pimentón and vegetables such as bell peppers. a classic poor man’s dish— the food of the transhumant ranchers who traveled the Meseta with their herds—migas are found across Spain and the dish has recently undergone a kind of gentrification, finding its way onto restaurant menus. Torrijas, or “Spanish French toast” (bread fried with cinnamon, cardamom and citrus zest), is most often enjoyed around easter week. Simple but satisfying, it is foods like migas, torrijas and cocidos that give central Spanish cuisine what chef José Pizarro describes as its “comfort food” qualities.

From The World on a Plate by Mina Holland, published on May 26, 2015 by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright by Mina Holland, 2015.

Leave a Reply