Family TableFavorite Staff Meals from Our Restaurants to Your Home

The best staff meals from Danny Meyer’s acclaimed restaurants—Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern, Maiolino, Eleven Madison Park, The Modern, Blue Smoke, Untitled at The Whitney, and more—simple enough for any home cook’s weeknight dinners, delicious enough for the most discriminating palates.

Some of the Best Food You’ll Never Eat in a Restaurant.

Danny Meyer’s restaurants are among the most acclaimed and beloved in the nation: Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern, Maialino, Blue Smoke, The Modern, and more, winners of an unprecedented number of James Beard Awards for outstanding food and hospitality. Family Table takes you behind the scenes of these restaurants to share the food that the chefs make for one another before they cook for you.

Each day, before the lunch and dinner services, the staff sits down to a “family meal.” It is simple, often improvised, but special enough to please the chefs’ discerning palates. Now, for the first time, the restaurants’ culinary director, Michael Romano, coauthor of the award-winning Union Square Cafe Cookbook, collects and refines his favorite in-house dishes for the home cook, served alongside Karen Stabiner’s stories about the restaurants’ often-unsung heroes, and about how this imaginative array of dishes came to be. Their collaboration celebrates food, the family itself, and the restaurants’ rich backstage life.

Some of the recipes are global and regional specialties: Mama Romano’s Lasagna, Dominican Chicken, Thai Beef, Layered Huevos Rancheros, and Southern Cola-Braised Short Ribs. Many highlight fresh produce, like Michael Anthony’s Corn Soup, Barley & Spring Vegetables with Pesto, Grilled Halibut with Cherry Tomatoes, Sugar Snap Peas & Lemon, and Plum & Apricot Crisp with Almond Cream. There are homey dishes like Turkey & Vegetable Potpie with Biscuit Crust and Streusel-Swirl Coffee Cake, and inventive, contemporary takes, like Cornmeal-Crusted Fish Tacos with Black Bean & Peach Salsa and a delightfully tangy Buttermilk Panna Cotta with Rhubarb-Strawberry Compote. What all these recipes have in common is ease and perfection.

Considered by the New York Times to be “the greatest restaurateur Manhattan has ever seen,” Danny Meyer is CEO of the Union Square Hospitality Group. His restaurants have won an unprecedented twenty-one James Beard Awards. His book, Setting the Table, was a New York Times bestseller.

Michael Romano is the culinary director for the Union Square Hospitality Group and co-owner of Union Square Cafe, which won a James Beard Award under his direction. With Danny Meyer, he wrote the James Beard Award-winning Union Square Cafe Cookbook and Second Helpings from Union Square Cafe. He was inducted into Beard Foundation’s Who’s Who of Food and Beverage.

Karen Stabiner is an adjunct professor at Columbia’s graduate school of journalism. Her work has appeared in Saveur, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Vogue, and Travel & Leisure. She is the co-author of The Valentino Cookbook.

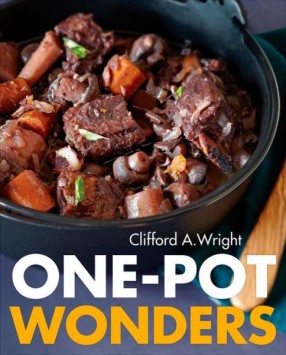

Michael Romano’s Secret-Ingredient Soup

4 to 6 servings

The secret ingredient in this satisfying soup is a small amount of cornmeal (polenta), just enough to thicken the broth slightly. It balances the substantial sausage and greens for a soothing cold-weather dish.

Aleppo pepper comes from the town of Aleppo in northern Syria; the flaky crushed sun-dried pepper has a slightly smoky flavor. It’s become easier to find in gourmet markets, but if necessary, you can substitute red pepper flakes.

2 tablespoons olive oil

¾ cup finely chopped onion

¾ cup finely chopped peeled carrot

¾ cup well-washed thinly sliced leeks

1 teaspoon finely chopped garlic

1½ teaspoons kosher salt

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

¼ teaspoon Aleppo pepper or red pepper flakes

8 ounces Italian fennel sausage (sweet or hot), casings removed

2 tablespoons medium-grind cornmeal (polenta)

5 cups Chicken or Vegetable Stock (below)

4 cups packed stemmed and coarsely chopped kale or chard leaves, or a combination

Grated Parmigiano-Reggiano for serving

Heat the oil in a large saucepan over medium heat. Add the onion, carrot, leeks, garlic, salt, black pepper, and Aleppo pepper and cook, stirring, until the onion becomes translucent, 8 to 10 minutes. Add the sausage and cook, breaking it up into small pieces with a wooden spoon, until no longer pink, about 5 minutes.

Drain off the excess fat, leaving about 2 tablespoons in the pan. Stir in the cornmeal. Add the stock, stirring, and bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer, covered, for 30 minutes, stirring occasionally.

Stir in the greens and cook for 15 minutes more, or until tender.

Ladle into bowls and garnish with grated Parmigiano.

Vegetable Stock

3 quarts

1 tablespoon olive oil

3 cups sliced carrots (about 1 pound)

3 cups sliced onions (about 12 ounces)

2 cups coarsely chopped Savoy cabbage (about 6 ounces)

2 cups well-washed sliced leeks, white and light green parts only (about 5 ounces)

1½ cups sliced celery (about 6 ounces)

1 medium head Bibb lettuce, cored and coarsely chopped

1 cup sliced peeled parsnips

3 garlic cloves, sliced

½ cup coarsely chopped fresh Italian parsley

2 tablespoons finely chopped fresh basil

2 fresh thyme sprigs

1 bay leaf

2 tablespoons kosher salt

1 tablespoon whole black peppercorns

1 russet potato, scrubbed and sliced

2 tomatoes, cored and coarsely chopped

Heat the oil in a large saucepan over high heat. Add all the ingredients except the potato and tomatoes and cook, stirring occasionally, until the vegetables soften, about 7 minutes.

Add the potato, tomatoes, and 3 quarts water and bring to a boil. Lower the heat and simmer, covered, for 40 minutes.

Strain the stock through a fine-mesh strainer into a bowl or other container, pressing on the vegetables to extract the maximum amount of stock. (The stock can be refrigerated, tightly covered, for up to 1 week or frozen for up to 3 months.)

Chicken Stock

3 quarts

5 pounds chicken bones, rinsed well under cold water

3 celery stalks, quartered

2 medium carrots, quartered (2½ cups)

1 large onion, coarsely chopped (2½ cups)

1 large parsnip, peeled and coarsely chopped (1½ cups)

¼ cup fresh Italian parsley sprigs

1 teaspoon fresh thyme leaves

1 bay leaf

10 whole black peppercorns

Combine all the ingredients in a large pot, add 4 quarts water, and slowly bring to a boil over medium heat. Skim off the foam that rises to the surface. Reduce the heat and simmer very gently, uncovered, for 4 hours, skimming the surface every 30 minutes or so and adding more hot water if the level gets too low.

Strain the stock through a colander and then through a fine-mesh strainer into a bowl or other container. (The stock can be refrigerated, tightly covered, for up to 2 days or frozen for up to 3 months; remove any hardened fat from the surface before using.)

Photo © Marcus Nilsson

Introduction

by

Michael Romano

When I was growing up, it was hard to see where family life left off and meals began—my best memories include both. My mother had six brothers and sisters, my father had four siblings, and I had a sister and lots of cousins.

My grandparents lived upstairs from us in our East Harlem tenement, and almost everyone in the extended family lived in the neighborhood. I don’t remember a weekend without a meal or without relatives.

And what food! Some Sundays when I was little, I’d be sent off to an aunt, or upstairs to my grandmother, and over time I got to see how every component of those endless dinners was made. The aunt who made ravioli had no room in her kitchen, so she opened up the ironing board, spread a tablecloth on it, and usedit as extra counter space. I was just about as tall as that ironing board, and I stood there as she filled the ravioli, sealed the edges, and lined them up, counting off how many I was going to eat.

They were all so good, but my favorites were the pillowy ones filled with creamy fresh ricotta. My interest in her food was rewarded when my aunt appointed me to test the spaghetti to see if it was done. She taught me how to bite into a strand and know, right then, yes or no. Looking back, I guess I was setting my feet on the path to a food career without even realizing it.

When I was thirteen, our family began to migrate to the Bronx—first an aunt and uncle, then my grandparents, and then us—and the weekly Sunday family meals continued until I went to college. Even then, food was as central as it can be to three roommates who suddenly have no parents around to feed them. I moved in with two high school buddies, one of them the local butcher’s son, and while we didn’t put in the kind of time my mother did, we ate well.

I started college without much of a sense of where I was headed, but to help make ends meet, I worked as the frozen drink man at Serendipity, an Upper East Side restaurant where frozen hot chocolate, my primary responsibility, was the most famous item on the menu. There was no official family meal, no time when we sat down together to eat; we grabbed food on the run whenever we had the chance. But the family feeling was certainly there. The owners of Serendipity saw potential in me that I hadn’t yet seen myself—a genuine love of food, and no fear of hard work—and they arranged a meeting with James Beard for me. It was just the sort of life-changing event you might imagine. I arrived at his townhouse not knowing what to expect, and I left with an impatient passion. Thanks to his encouragement, I knew I had to get started on my life in food, and fast.

I dropped out of college and enrolled in a two-year food program at New York City Tech. A year later, I was on my way to three months of study in Bournemouth, England—and some of the worst food I’d ever eaten. If I hadn’t fully appreciated the joys of a great homemade meal with family and friends, I certainly did after three months of deprivation. At school, we worked with beautiful ingredients—grouse, Dover sole—but the professors ate the dishes we made, while we had to settle for the staff cafeteria, which specialized in starchy, overcooked, bland food. It was an odd, demoralizing notion, asking people who live to cook wonderful food to eat one bad meal after another, and it unified us only in our desire to get up from the table and go back to work.

As soon as I finished my studies, I headed to Paris—like Moses traveling to the Promised Land—and I landed a stage, a kitchen apprenticeship, at the Hotel Bristol. The food at family meal was the opposite of what I’d had in England— it had to satisfy the demanding sous chef—but the tension that pervaded our twice-daily meals made enjoyment impossible. The chef ate with the other hotel executives, never with us, and the front-of-the-house staff ate by themselves. The kitchen staff sat at a long table, with the sous chef at the head and the rest of us in descending order of importance according to our stations, down to the lowest of the low at the far end.

I still remember the day the sous chef took a bite of cauliflower, hesitated, and spat it out. He glared down the table and asked who had made it. An apprentice, a kid in his teens, said that he had. The sous chef gestured for him to approach. Meekly, the boy made his way to the head of the table—and, just like that, the sous chef punched him in the chest.

The boy just turned and walked back to his seat, which to me was the oddest part of the incident. Nobody made a big deal out of a kid getting punched for a disappointing vegetable. It was business as usual—hardly the most conducive atmosphere for what was supposed to be a break in a long day of work.

After more training and work in Paris, southwestern France, and Zurich, I went home and started working in New York City restaurants. I became the first American executive chef at La Caravelle, a legendary French restaurant in midtown Manhattan, where I supervised a kitchen full of trained chefs who expected the same type of high-quality family meal I’d had at the Bristol—minus the fisticuffs.

When Danny Meyer asked me to run the Union Square Cafe kitchen in 1988, I brought along two traditions that mattered to me: I wore a suit to work, as I had at La Caravelle, a habit no one else was interested in adopting, and I insisted on a sit-down meal twice a day for my restaurant family, one that would bring them together rather than keep them apart. That was a far more popular idea. Some of the staff had come from restaurants where they had just enough time to run out for fast takeout on their breaks. Some had had jobs where they ate out of quart containers at their stations or waited to eat until they had finished their shifts.

The rules for our family meal were simple: It couldn’t be fancy or complicated, but it did have to be full of flavor. People had to sit down to eat, with everyone gathered in the same room—front of the house and kitchen staff together. That’s how we started, over twenty years ago, and it’s what we’ve done at each of the Union Square Hospitality Group’s restaurants ever since, whether it’s a meal for fifty at Gramercy Tavern or a meal for ten at Untitled at the Whitney.

To some of the staff, sitting down together seemed a luxury; to me, it was essential. People work better when they take a break. I don’t buy the notion that stopping makes it harder to get started again. And I rail against the idea of, “No, I’m too busy, I’ll grab something quick in the kitchen.” I say, “You think you’re saving time and getting more work done, but you’re not eating or working as well as you would if you took a break. Sit down and eat. You’re going to be more productive. Don’t ask your body to multitask.”

I think that’s true for your family as well. It’s always good to take a moment to stop, to sit down and catch your breath over food and conversation, away from your desk, your electronics, your to-do list, everything but what’s on your plate and the other people seated at the table. The challenge for the home cook is to keep meals fun when you’re strapped for time, on a budget, and in danger of repeating the same familiar dishes again and again. Family Table is intended as a happy remedy, offered by cooks who operate under similar constraints but have the benefit of experience in a professional kitchen. We are sharing our family meals and the knowledge that went into creating them in the hope of inspiring and informing yours.

And when I say “we,” I mean it: This collection of recipes comes from about four dozen contributors, from sous chefs to prep cooks to porters, from cooks with classical training to cooks who learned everything on the job. The only common denominator is enthusiasm and a tasty idea. This is home cooking at its best. Some of the dishes are staffers’ personal family favorites, a parent’s or grandparent’s specialty updated with accessible, market-fresh ingredients and clever techniques. Some are inspired improvisations, the result of a cook’s ability to look at a collection of ingredients and figure out how to make them harmonize in a new way. And some are reconsidered classics, a standard preparation made just a little bit better.

The result is a world tour of various cuisines, with some recipes that may be completely new to you and others that may look familiar but come with a twist. And because the original recipes were made to serve dozens of people, all of these adapt easily to home entertaining. To celebrate our family, we also offer stories of life behind the scenes, which Karen Stabiner collected, about both chefs whose names you know and people you never see. Here you’ll find great dishes and stories from the whole family, including former members of the group, like Eleven Madison Park and Tabla.

Even after all this time, family meal is still a draw for me. Sometimes I walk over to one of the other restaurants in the late afternoon, or I manage to schedule a meeting around the time that the midday meal comes out. It’s a chance for me to spend time with my restaurant family, both the people I’ve grown up with professionally and the next generation we’re proud to be bringing along. In a funny way, I’ve come full circle: Like that little guy counting ravioli and looking forward to dinner with my relatives, I still can’t tell where family leaves off and the meal begins, which is just the way I like it.

I hope that these recipes inspire your family as well to sit down together at the table.

Excerpted from FAMILY TABLE, © 2013 by USHG, LLC, and Karen Stabiner. Reproduced by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply