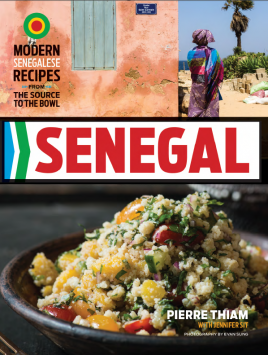

SenegalModern Senegalese Recipes from the Source to the Bowl

Senegal will transport you deep into the country’s rich, multifaceted cuisine. You’ll feel the sun at your back and the cool breeze off the Atlantic, hear the sizzle of freshly caught fish hitting the grill, and bask in the tropical palm forests of Casamance. Inspired by the depth of Senegalese cooking and the many people he’s met on his culinary journey, these recipes are Pierre Thiam’s own creative, modern takes on the traditional. Learn to cook the vibrant, diverse food of Senegal, such as soulful stews full of meat falling off the bone; healthy ancient grains and dark leafy greens with superfood properties; fresh seafood grilled over open flame, served with salsas singing of bright citrus and fiery peppers; and lots of fresh vegetables and salads bursting with West African flavors.

Pierre’s first book, Yolele!, introduced Senegalese food to the world, and now Senegal takes a deeper dive, showcasing the ingredients and techniques elemental to Senegalese cooking, the food producers at the heart of its survival, and the unique cultural and historical context it exists in. You’ll meet local farmers, fishermen, humble food producers, and home cooks each with stories to tell and recipes to share and savor. You won’t just be learning to make a few dishes, you’ll learn about the Senegalese people, the stories of their past, and importantly, the issues they face today and tomorrow. This is the food of Senegal, from the source to the bowl.

Pierre is the owner of Pierre Thiam Catering and author of Yolele!, the first Senegalese cookbook in English.

Pierre Thiam talks to us about his home country of Senegal and its rich culinary traditions that he has documented in his new book.

BAF: Maybe you could just tell us a little bit about Senegal.

Pierre Thiam: Senegal, geographically is located in the northwestern coast of Africa. That obviously influences the food, because lots of seafood, one of our main protein. South of the Sahara desert, so the northern part of Senegal is mostly semi-desert no grains, but we would be eating rice and millet and Fonio, and sorghum. The rice is imported most of the time. The southern part is more tropical, that’s where we have the rice-growing culture. It’s also coastal, so lots of seafood as well.

Senegal was also colonized by the French, so you have a strong French presence, till now. It happened to be, because of it’s geographical location, it happened to be the entrance, the natural port of entrance into Africa. You have not only the French came through the shores of Senegal, but we also had the Portuguese and they still have a presence in the south. There’s a language spoken in the south, that’s the one actually my mother used to speak with me, because she’s from that region. That’s the Portuguese Creole, that’s still very much alive there.

The cuisine of Portugal can be also felt in that part of the south of Senegal. We also had an English presence in the center of Senegal, it’s funny, we’re still divided by this tiny little country called The Gambia. That’s an English colony and that’s still an English-speaking country. You have all these western influences. You also have the neighboring countries, Mauritania in the north, the Sahara desert, we have Mali in the West, we have Guinea. Those different countries also have a strong communities in Senegal, and with those communities, both their food, their cuisine.

BAF: Can you tell us a little bit about the food?

Pierre Thiam: The food have different influences. A couple more that I mentioned, the minority communities that are still very strong in terms of their food influence. The Vietnamese who arrived because we have the same colonial past, the French here. At the time of colonization, there was a French battalion in the army that was mostly comprised of Senegalese soldiers, only Africans. Those guys would be sent to quell any type of tensions or rebellions in the French colonial empire. It happened that there was a strong community of Senegalese soldiers in Vietnam, who was called Indochine at the time.

When the French left the (Vietnam) war, the Senegalese returned to Senegal with a large number of Vietnamese, who were running away from the hell that was happening there. When French left, the American came in. Anyway, so that’s how those guys arrived in Senegal and they arrived with their cuisine. Me particularly, I was fortunate because one of them happened to be a friend of my parents, he became my God Father. He’s had as strong an influence on my food as well, because I always go to his cuisine, he loved to cook. He was the only man I would see cooking in Senegal, cooking in the gender-based activity. He not only was a great cook, he was a man cooking, which was a rarity.

The other influences, so I mentioned the ingredients, the protein mainly is fish, the grains are rice millet, fonio and sorghum. The national dish of Senegal is one that you would see pretty much at every household at lunchtime, it’s called thiebou jen. It translate rice and fish, but it’s really not doing it justice. It’s like a dish that’s a bit like paella in its appearance. It’s really this bright red rice with vegetables and fish.

The fish is stuffed with spice mixture that has parsley and scotch bonnet and garlic, and a seasoning, it’s called Rof. It’s a spice mixture. The recipe for Rof varies from household to household, but it’s a very fresh and very spicy filling and stuffing. You stuff the fish with that spice mixture. You cook that fish in the tomato broth.

That tomato broth also have vegetable that will be served with the rice dish. The vegetables from vary from cabbage to yucca, to okra, and those vegetables cook slowly with the fish in that broth, so it enriches the broth. There is also in the broth, what we call the Funky Element of our cuisine, and that’s known now as umami. That’s fermented ingredients. We tend to ferment different things in Senegal, like conch. We ferment it and it adds an interesting flavor to that broth.

We also add dried fish in it and we ferment locust bean called dawadawa in some parts of Africa and they do it too in Senegal, but that’s the locust bean from a tree and it’s fermented because of strong flavor. Those ingredients can be easily substituted with a sauce, Asian fish sauce, if you don’t have access to those fermented ingredients. You just add sauce to the broth.

Once that broth is completely flavored with the fish that’s cooking it and the fermented ingredients, and the vegetables, those are all scooped out to allow to cook the rice. The rice is now cooked into that same broth, so imagine the intensity of the flavor in addition with, it’s a tomato broth. The right term is really bright red color and cooked in that broth, and then served with the fish and those vegetables in a big bowl because they eat traditionally around the bowl. The Senegalese tradition is to eat with family and friends around the bowl.

Also always remember that when you serve the rice, and the bottom of the pot that cook the rice, there is that crust it is always served on the side as well. That’s an elaborate lunch that you have every day. It’s slow cooking at its best. Woman start cooking in the morning and making sure lunch is ready. Around noon the whole country stops functioning and everyone goes home to share the lunch. That’s the tradition.

You’d see everyone seem surprised at noon time at 1:00. The streets are empty and you can expect to have an amazing thiebou jen for lunch, most of the time. We also have other recipes like mafé that’s another popular one, that’s the peanut sauce. This you serve with either lamb or chicken.

BAF: There are so many interesting diverse recipes from the different parts of the country. How did you go about compiling everything?

Pierre Thiam: Yeah, lots I couldn’t fit in. I followed the path that we took, me and Evan Sung the photographer of the book. We traveled from north to south, we did 4 different trips to Senegal, and we segmented the region. As we were traveling, the idea for me was to meet those producers, food producers or farmers, or pheasants or fishermen. As you see in the book, they are like this highlights, where I give those people the words and I describe their craft or whatever they are doing with their trade.

This was really the inspiration, most of the inspiration for the recipes, because they would go from their produce and develop recipes either revisit the traditional recipe the way it’s been done for hundreds of years, or just imagine recipes based on these produce that I would encounter through the travels from north to south.

BAF: You have section in the book about ‘sacred food’ Is that something that is still strong in the culture?

Pierre Thiam: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. In the south like I say, it’s completely different than the northern side of Senegal. It’s very lush and tropical, and culturally speaking, that’s the part that’s holding strong to it, tradition, so sacred food is definitely part of the life there.

BAF: What’s your background? How did you come to be cooking in New York and writing cookbooks books?

Pierre Thiam: I started really not even considering food as a career option, because again, I said because my cultural background. In Senegal, cooking was women’s domain. I was a student in physics and chemistry at Dakar University. Until this one year late 80s, where we had a strike. Back in the days in the 80’s we had lots of strikes. I couldn’t even tell you why I was striking. We were just were just young students and I would just follow flow.

The strike movement became so long that the government had to call a year in French. It’s called année blanche, that translates blank year. That means we had to start over. The next year there is no exams, no exams were recognized and we had to start over. To me, that was the excuse to just follow up on my dream. I always wanted to leave. I always wanted to come to the United States, and this was really the perfect excuse to convince my parents to accept that I could try to find an application for school in the United States. I did find an application, which allowed me to have a student visa.

I was heading to a school called Baldwin Wallace College in Ohio of all places. I never made it to Ohio. I came here on my way, sincerely thinking I was going to get there, and decided to visit a friend that I knew in New York because everyone wants to come to New York once in their lifetime, so that was my opportunity. I decided to visit there for 2 weeks, and these 2 weeks lasted until now. It’s 26 years now I’ve been here.

Actually, what happened is a set of circumstances. I lost my money, first of all, in a mysterious way. That’s why I had to find a job right away to keep going to Ohio. I was fortunate that a friend of mine was working at this restaurant in the west village, in Manhattan. He had an opening for bus boy. He introduced me to the boss and I got that bus boy job.

That way everything changed because that restaurant was really doing some great foods, and as a bus boy I could see, but not only as bus boy, but I was taking the food from the kitchen to the table and looking at these amazing dishes. Another shocking for me was that everybody in the kitchen were men. There were not a single woman in the kitchen, which is something I wasn’t prepare to get, because I always saw women in the kitchen where I was coming from, and now here are these men, creating this amazing food.

I was naturally attracted to this environment. I became very friendly with the guys in the kitchen, and the chef allowed me to the dish-washing shift when I wasn’t on the bus boy shift. That’s how I gradually get into the kitchen. I started to wash dishes and washed pots and dishes. Next thing you know, I was just helping out doing the prep, peeling vegetables, chopping, washing grains and stuff. It was a natural process.

From there, I went to the garde manger position, which is the salads and dressing the dessert, from there, just nesting, and the opportunity opened up for the grill. I was on the grill. It was the roughest time. That’s when I thought I was going to give up, but the chef was really, really great. He was like a mentor me. Just started to guide me for my interest. I was also realizing that I was doing the chemistry and cooking because my background was physics and chemistry, and I was also seeing the connection. I realized that this is really what I was interested in.The chef was very open-minded. He perceived this in me and he started to guide me into certain books. I loved to read at the time, and he guided me to certain books to focus on, which I did, in cooking and training myself, self-training myself in the kitchen, when I was doing the prep time. I grew from that restaurant to go into another restaurant, that was an Italian one this time. Now I was a line cook, learn those skills from that Italian restaurant.

I went to French bistro, Jean-Claude that had just opened in Soho. I opened matter of fact, with that kitchen crew. That was another style of cuisine that was in my CV, that I added to it with the restaurant, another place in Soho another restaurant called Boom, that was serving global ethnic cuisine. It was back in ’92, and Boom, the idea was to visit ethnic cuisine and introduce it to its clientele. We’re going from North Africa to Southeast Asia.

At Boom, I became a sous chef. Then as a sous chef I was asked to introduce also dishes from Senegal, from wherever, but Senegal became my natural source of inspiration. The first time I introduced Mafe, and the reaction was just amazing, it was a special, and it was amazing. People reacted in a way that just convinced me that I should really look back into this cuisine.

That’s when I started to exchange recipes with my mom and gradually take those influences, adding it to all the other influences from my background, all those other restaurants that I have worked in, and adapting it to this restaurant, to the kitchen. That’s how it happened, and I am still doing that.

BAF: You didn’t grow up cooking. It sounds like it’s something happened here in New York.

Pierre Thiam: Yeah, it was something that happened here in New York. I didn’t grow up cooking. The only thing I ever remember cooking in Senegal … Well, actually, I was a Boy Scout, so that’s the only time I was in the kitchen, as a Boy Scout. Those were my early memories. Then one day I just simply attempted to bake a cake for my sister’s birthday, because my mom had a cookbook collection, and that’s just my early memories of me and cooking, was just to look at the photograph of this cookbook collection and just drooling over those pictures, that inspired a six year old boy instead of doing soccer with my friends in the street. That was the closest I got into the kitchen, until as Boy Scout, I got into this cooking and really horrible stuff at the time. As a Boy Scout it was just overcooked rice and stuff, it was all good. It was just training. Yeah, so that’s pretty much it. Yeah, the cake I tried to do for my sister’s birthday, I loved it, but I didn’t think it was anything special. It was just a pound cake.

BAF: It was a big deal at the time.

Pierre Thiam: It was a big deal at the time, huge.

BAF: Can I just ask about the photographs in the book, because those are absolutely beautiful?

Pierre Thiam: Yeah, he did a great job. His name is Evan Sung. I was fortunate to just collaborate with him. He had this way of capturing the essence of the culture. We had the moments, conversing about what we wanted this book to be. Then he would just land in Dakar and go on his own. The great thing about it is, he speaks French, just a little bit, but he could communicate easily with people. That was just people that even relax. So that’s he was able to capture these amazing pictures of people just being themselves. The food pictures also were amazing. He was just a great one to collaborate with.

BAF: There’s really no such thing as ‘African cusine’ in general. It’s like saying ‘European food’.

Pierre Thiam: I hope this book also help dispelling the myth about that African cuisine and just open a window, give some more information to the reader about just the diversity and the wealth of the abundance of our cuisine, and introduce them to Africa in a way, but through one country.

BAF: If someone were to ask you about Senegal, what would be the one thing you would tell them?

Pierre Thiam: About Senegal, I would say the one thing, and this is the thing we value the most, this is our core value, the hospitality. The hospitality symbolize with how we share the food. We have a word for that. We call it Teranga. Teranga is concept for hospitality, but it is much more than hospitality. It’s like how the guest is treated with such honor. The guest can be expected or unexpected, but anyone who just enter through your door, enters your house, becomes the most important person in that house. You share with them the best of what you have.

BAF: That’s a very nice tradition.

Pierre Thiam: It is, absolutely it is. It really is. We have this strong belief that the more you share, the more you receive, especially when it comes to food, so you really receive the shock when you come to Senegal and people would insist on having you come and share their food. Because not only they mean it, but they also know that the more they share, the more their bowl will be plentiful. They will always have more food in their bowl, so that’s just the way to guarantee that they won’t go hungry, by sharing with you.

BAF: You’ve just finished this terrific book and you have your catering company so what’s next for you?

Pierre Thiam: What’s next? Right now at the moment, I am getting ready to go to Nigeria, where I’ve been working on a new restaurant, actually. I am consulting at a restaurant that’s opening in December. I’m doing an institute in Dakar, that’s like a culinary institute. I am collaborating with a group from Boston University, called the West African Research Center. We’re organizing an institute, plus a culinary trip to Senegal at the end of January, early February. It should be really, really interesting. We have a great itinerary. It’s going to be more than just sightseeing and markets, and stuff, but getting deep into the food culture of West Africa.

Pierre Thiam’s passion for his homeland is palpable in his second cookbook Senegal. He promises to transport the reader into the vibrant and diverse culture of Senegal through pictures, history, food, and teranga or “hospitality,” and he delivers ten-fold. As an accomplished chef, Thiam gives a masterclass in what will probably be a food trend in the United States not too far into the future—West African cuisine. Get ready to pack your bags for this culinary adventure. –Carla Hall-author of Carla’s Comfort Foods and co-host of “The Chew”

Mango Fonio Salad

Grilled Piri Piri Prawns & Watermelon Salad

Chocolate Mango Pound Cake![]() Mango Fonio Salad

Mango Fonio Salad

Bursting with fresh herbs, lemon, and mango, and super easy to throw together, this healthy grain salad would make a great addition to picnics or potlucks as a side for grilled fish or meat or as a vegetarian main. Think of this salad as a template to which you can add any number of your seasonal produce favorites.

Serves 4

Juice of 2 lemons

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 cup olive oil

2 cups cooked fonio (page 150) or quinoa

1 bunch parsley, leaves finely chopped

1 bunch mint, leaves finely chopped

1 ripe mango, peeled, pitted, and diced

½ red onion, finely chopped

1 cup red and yellow grape tomatoes, halved

1 small cucumber, seeded and diced

½ cup Spiced Cashews (page 87; optional)

›› In a small bowl, combine the lemon juice with the salt and pepper. Slowly pour in the oil, whisking to emulsify.

›› Place the fonio in a large bowl and add the parsley, mint, mango, onion, tomatoes, and cucumber. Toss well and generously fold in the vinaigrette to taste. (You may have some left over.) Top with the spiced cashews (if using) and serve immediately.![]()

Grilled Piri Piri Prawns & Watermelon Salad

This fiery piri piri recipe is Mozambican-inspired and it is, to me, the best way to serve prawns. If you prefer, the heat of the marinade can be toned down by using less Scotch bonnet, but don’t fear, the watermelon’s fresh sweetness will attenuate its burning effect. I like to serve the prawns with the shells on to keep all the flavors, so I encourage eating with your fingers, which I’m sure you’ll be licking clean.

Serves 6 as a starter

Prawns

¼ cup vegetable oil

4 garlic cloves, finely chopped

1 Scotch bonnet pepper, finely chopped, or 2 tablespoons cayenne pepper

1 teaspoon fine sea salt

1 teaspoon sweet paprika

18 prawns (shells and heads on, if possible) or large shrimp

Watermelon Salad

6 large wedges watermelon, about 1½ inches thick (rind on)

½ cup olive oil, plus more for brushing

Juice of 2 limes

1 tablespoon fine sea salt

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

½ cup thinly sliced red onion

1 large jicama, peeled and cut into ½-inch cubes (see Note)

2 tablespoons chopped fresh cilantro

2 tablespoons chopped fresh mint

Pinch of Hibiscus-Chile Salt (page 219; optional)

›› To prepare the prawns: Combine the vegetable oil, garlic, Scotch bonnet, salt, and paprika in a large bowl. Add the prawns and toss well. Cover and marinate in the refrigerator for at least 2 hours or up to 24 hours.

›› To prepare the salad: Preheat the grill or a grill pan to hot.

›› Blot the watermelon wedges with paper towels to remove excess juice. Lightly brush with olive oil and grill for 1 to 2 minutes on each side, until lightly charred. Set aside to cool. Cut off and discard the watermelon rind. Cut the flesh into 1-inch chunks.

›› In a large bowl, combine the lime juice, salt, and pepper. Slowly add the olive oil, whisking constantly to emulsify. Taste and adjust the seasoning. Add the onion, watermelon, jicama, and 1 tablespoon each cilantro and mint. Toss well.

›› Drain the prawns and discard any leftover marinade. Grill the prawns for 2 to 3 minutes on each side until just pink.

›› To serve, spoon a serving of salad into each bowl and arrange the grilled prawns on top. Top with the remaining mint and cilantro and a pinch of hibiscus salt. Serve immediately.![]()

Chocolate Mango Pound Cake

This rich, moist mango cake is one of my favorite desserts during the rainy season in Senegal, when it seems as if mangoes are growing from every other tree, yet I can never get enough of them.

Serves 6 to 8

¹⁄³ cup unsalted butter, at room temperature, plus more for greasing the pan

1 cup all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon baking powder

¼ cup honey

½ cup packed light brown sugar

½ teaspoon salt

1 cup finely chopped ripe mango (preferably the less-stringy champagne variety)

½ teaspoon vanilla extract

1 large egg

½ cup plain full-fat Greek-style yogurt

1 cup semisweet chocolate chips

›› Preheat oven to 350°F with a rack in the center position. Grease an 81/2 by 41/2-inch loaf pan.

›› Mix together the flour, baking soda, and baking powder.

›› In the bowl of a mixer, combine the butter, honey, brown sugar, and salt. Beat with the paddle attachment on medium-high speed until light, about 5 minutes. Add the mango and vanilla and beat, until just combined.

›› Reduce the mixer speed to low and beat in the egg. Slowly beat in the flour mixture; stop mixing as soon as it’s combined. Add the yogurt and mix just until it’s incorporated, about 5 seconds. Fold in the chocolate chips with a rubber spatula.

›› Transfer the batter to the prepared loaf pan. Bake on the center rack for 45 minutes or until a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean.

›› Cool the cake in the pan on a rack and serve.

Leave a Reply