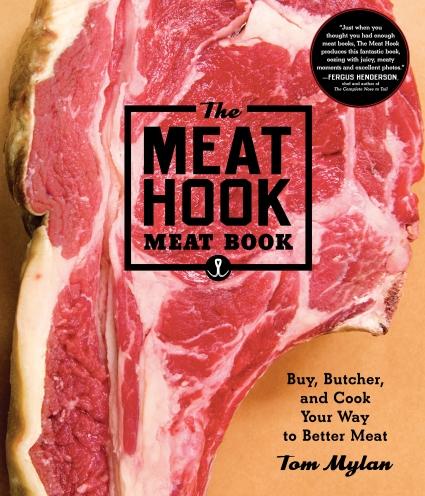

THE MEAT HOOK MEAT BOOKBuy, Butcher, and Cook Your Way to Better Meat

Getting what you want, not just what a grocery store puts out for sale—and tailoring your cuts to what you want to cook, not the other way around.

Buying large, unbutchered pieces of meat from a local farm or butcher shop means knowing where and how your food was raised, and getting meat that is more reasonably priced. It means getting what you want, not just what a grocery store puts out for sale—and tailoring your cuts to what you want to cook, not the other way around. For the average cook ready to take on the challenge, The Meat Hook Meat Book is the perfect guide: equal parts cookbook and butchering handbook, it will open readers up to a whole new world—start by cutting up a chicken, and soon you’ll be breaking down an entire pig, creating your own custom burger blends, and throwing a legendary barbecue (hint: it will include The Man Steak—the be-all and end-all of grilling one-upmanship—and a cooler full of ice-cold cheap beer).

This first cookbook from meat maven Tom Mylan, co-owner of The Meat Hook, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is filled with more than 60 recipes and hundreds of photographs and clever illustrations to make the average cook a butchering enthusiast. With stories that capture the Meat Hook experience, even those who haven’t shopped there will become fans.

Tom Mylan is the executive chef and co-owner of The Meat Hook. Opened in 2009, The Meat Hook is a local, sustainable butcher shop housed in the popular Brooklyn Kitchen, the largest cooking school for home cooks in New York City. A leading force in the national obsession with meat, butchers, and butchering, Tom has contributed recipes and stories to Food & Wine, Gilt Taste, and Gourmet and has appeared on Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations. Chow.com called him one of the 13 most important people in food in 2010, andNew York magazine honored him as one of the “Curators of New Brooklyn.” He met his wife, Annaliese Griffin, when they both worked at Murray’s Cheese. They live in Brooklyn.

It might seem counter-intuitive for a former vegetarian to be an authority on meat. But Tom Mylan is just that. The co-owner of Brooklyn’s Meat Hook butcher shop has be come a leading voice in sustainable and humane farming. He was kind enough to take some time out from his busy schedule to talk with us about his latest venture The Meat Hook Meat Book.

Booksaboutfood.com (BAF): Have you come across anybody saying, “Why a meat book? Why now?”

Tom: No, but to be fair, I live in kind of a bubble… Brooklyn. I guess New York and San Francisco and Portland are like it’s become actually cool to be into meat as long as it’s ethically sourced and grass-fed and all this kind of stuff, so no, I have not, since the book has come out, had anybody really say anything negative about eating meat.

I think it helps that in the introduction of the book, I talk about that I didn’t eat meat for a certain period of time once it became apparent to me the conditions under which factory farm raised animals, what they were subjected to, but then I moved to New York and there was a farmers market and I learned, “Oh, there’s local food. You can actually eat meat that’s outside of the food industrial complex or what-have-you.” I think that definitely helps because I have been on both sides of the fence about it.

BAF: You’ve had an interesting transformation yourself because you were, I don’t know if you’d say a diehard vegetarian, but certainly a vegetarian. Not the first choice of person to be operating a butcher shop.

Tom: Right, but the thing of it was like a political and ethical sort of thing. It was a bout like I didn’t want to participate in a system that basically en masse tortured animals through their short, horrible lives just so I could have a really cheap pork chop or something. I didn’t not eat meat because I thought eating meat was wrong. I just thought eating meat from animals that were treated a certain way was wrong, and obviously, once I discovered traditional farming methods, small farm, pasture-raised meat, I went from somebody who didn’t eat any meat to somebody who ate meat sparingly. I still eat meat kind of sparingly, despite the fact that I own a butcher’s shop.

BAF: It was really a conscientious decision as opposed to health-related.

Tom: Right. I was so transformed by that moment when I discovered, “Oh, there’s an alternative to this,” that I sort of became I think the right word for it might be like even evangelical about it, and that kind of directly, indirectly led to the butcher shop. Giving people access to that meats outside of the farmers market that’s only on Monday and Wednesday or something.

BAF: Did you have an ‘a-ha’ moment? You mentioned when the transformation came about, was there an epiphany of sorts.

Tom: Honestly, I was working at Murray’s Cheese in West Village. I had lived in New York less than a year at that point and I got my first real paycheck because they actually pay people pretty well there. Me and my then girlfriend, now wife, walked from Murray’s in the West Village to the Union Square Farmers Market and I was like, “Wow. There is an alternative to buying meat at the grocery store. There’s choice now, and that was really the aha moment.

BAF: You became a carnivore again.

Tom: Yeah. Again, the meat was much more expensive. It was like a $16 pork chop, but not only could I feel better about it because I knew where it was coming from and how it was raised … That’s the thing I’m trying to get across in the book…the fact that not only is it better for the environment and better for the animals and better for the local economy and all this stuff, but it tastes a lot better. I mean not a little bit better, like a lot better, like 150% better, and that was the other thing. I was just like, “Oh, my God. This tastes like something.” I don’t have to slather it in some sort of bottled marinade or something to make it taste like anything.

BAF: It seems that the local butcher is, in some ways becoming a thing of the past. Is this something you’ve found or are people surprised that there’s a butcher shop opening up?

Tom: I think that up until the point that my partner, Brett Young, and I opened the butcher shop, Marlow & Daughters, for Andrew Tarlow, I think it very much was dying out. It was very much becoming a thing of the past sort of like neighborhood butcher shop because people were really thinking about food more in terms of cost. Why would you go and pay more to go to a butcher shop even though the meats better there? I’m just going to go to the supermarket and buy the family pack that’s five bucks or something. I really think that the thing that’s made opening that butcher shop and then we left there to open our own butcher shop, The Meat Hook, the thing that’s making the small butcher shops have a comeback now in the last five, six years is really that people want to eat better meat. James: Your shop, it’s all manner of meat. It’s not just beef or pork. It’s a bit of everything.

We don’t specialize in game or anything like that. We got a chance to work with a lot of different farms when we opened Marlow & Daughters and we sort of cherry-picked the best ones and chose to have a relationship with them, so we have two pig farms, one main beef farm, and then a co-op, and then a chicken farm that we work with, so we don’t do a lot of things outside of the normal beef, pork, chicken, lamb sort of stuff.

We can get anything that anybody wants because we want to be a full-service butcher shop. We don’t want to be like, “No, we’re not going to do that. We’re not going to help you find that,” but it doesn’t make up the majority of our business. I would say it’s less than a half of percent of what we do is that kind of stuff.

BAF: What was the reception, to your opening, like?

Tom: The butcher shop was more of a response to a need. We weren’t just opening a butcher shop and building the baseball field, “They will come” kind of a thing. We were responding to people’s desires. We had a really great response. People were like, “Oh, thank God. I’ve been waiting for this. Thank you so much.”

BAF: You also offer classes.

Tom: Through The Meat Hook, we do a pig butchering, a beef butchering class. It’s two different days or nights, that class. Sausage making, meat cooking, and then, through The Brooklyn Kitchen, where we do our meat classes, they also offer almost any class you can think of: Pizza making, bread baking, knife skills, Chinese street foods, kind of like all over the place.

BAF: At one (in the book) point you’re talking about the different cuts of meat you found in your travels, like the base of the tongue you mentioned in Japan is used as the steak. Is this something you’re trying to promote these, I don’t want to say newer cuts, or alternative, for lack of a better word, is this something that you’re giving people an opportunity to try or letting people know about?

Tom: Yeah. What it is basically is the same way that we’re evangelical about locally, sustainably raised meat, we only bring in whole animals. We don’t buy anything like bits and pieces because that’s the nature of knowing where it comes from, not dealing with a distributor in this guy and that guy, so we get all those pieces. It’s in our best interest to try to promote these lesser known cuts, and we’ve been really successful with it. A lot of people are very open-minded or at least curious. They might only try it once, but we definitely are really keen to share the good news or whatever with our customers and then through this book with sort of people nationwide.

BAF: What was your goal in creating this book? What was your objective?

Tom: I think I wanted it to be there’s more than a few butchering books that came out before this book. A lot of them focused more on the butchering aspects and less on the how to think like a butcher kind of thing, and that’s really what I’m trying to get across. All the recipes are very strategic. They’re teaching all of these different skills, teaching all these different cooking methods, teaching all these different ways of thinking about where the meat comes from on the animal and what it does when the animal’s walking around and then how that dictates how you cook it.

Really, the book is designed in a sort of somewhat stealthy way that if you cook your way through it, you come away with a pretty good general understanding of not just how to cook these different recipes, but really, how to think about meat, how to think about where things come from on the animal, the different types of cuts.

“Oh, what’s the best cut? What’s the best cut?” There’s no best cut. It’s what’s the best cut for the particular thing you are trying to do. If you’re trying to make a ragu, you don’t want to use tenderloin, but also, if you’re grilling, you don’t want to grill beef shank and explaining to people and also showing them through the recipes what these different parts are and why they are the way that they are and why this cut is better for this thing than another.

BAF: It is a really nice hands-on book. It’s a real ‘how-to’, but not being hit over the head with it.

Tom: Yeah. I really wanted this book to try to get butchering out of this sort of niche market ghetto kind of a thing and be more of a pop book that could appeal to a broader audience. There’s a lot of butchering and meat books that are out there that are very much written for the people that are already interested in this, sort of Michael Pollan book-toting people, and I really wanted to get it out to the larger world so it would be like something that somebody would buy for their dad for Father’s Day, and he’d reading and be like, “Oh, pastured beef,” or “Oh, this is the way that you do that.” I really wanted to make this a larger audience book.

I definitely want it to be fun, and I try to make all the text, make everything seem very approachable and explain in a sort of a very human way. Basically, the book was more or less already written by conversations I’ve had with our customers across the counter and this book is very much like one long conversation across the butcher counter, like you were a customer and I was just talking to you and explaining all this stuff and the things, giving recipes. All the language is very conversational.

BAF: People generally seem to want to know where their food comes from and taking more care of it. It’s in some way food because we’ve lost our way a bit because we don’t have these small butcher shops as much anymore.

Tom: Yeah, or independent markets or any of that stuff. It used to be that even when you went to the whatever, the supermarket, they were buying that stuff locally, the produce and the meat and all that kind of stuff. It’s interesting talking earlier about traveling and looking at the different ways that people in different countries do their food. You can go to a giant supermarket in like, for instance, Australia and in the back, there’s a massive butchering area where they have all the beef is locally sourced and there’s a small army of butchers breaking down whole carcasses, and then it’s going to go out into some trays out like a regular supermarket, but it’s actually the real deal. It’s interesting that they still have that culture there.

Britain is also another interesting place. I was actually just talking the other day with a guy that’s going to open a butcher shop just outside of London and it’s really interesting that, thankfully, small butcher shops never totally died out there, but they’re now making a comeback. With all the butcher shops that are there, they’ve been doing it what I would call the right way, whole carcass stuff, for a really long time.

BAF: The butcher shop was part of a community. It was part of the connection of people cooking.

Tom: Yeah, I think the community thing is huge. Brooklyn despite the fact it’s whatever it is, the third largest city in America or whatever, North Brooklyn is very much like a small town and the customers, our loyal customers that come to the shop and they also shop at other local businesses. They go out of their way to not go to Starbucks. They go to a place that’s actually owned by a person with a face. We run into our customers out at bars or at a party. A lot of our customers, they’re not just our customers. They also have become really good friends of ours. We go to their birthday parties and they come to our book release thing.

That sort of “you’re the help and I’m the customer” kind of a thing is really not a thing that happens here. It’s really dissolved and it’s really like community is a really good feeling, and I think that’s something that drew me here, now 12 years ago, is I was looking for that sense of community. I wanted to get out of the anonymous suburbs.

BAF: What was your background before Brooklyn?

Tom: I’ve always worked in food. It’s kind of one of those things I used to think that was a curse because working in food was certainly not cool back in the early mid ‘90s when I got my first job working in food when I was 15 working at a pizza place. My best friend worked there and he got me a job there, but once you worked in food, you couldn’t really do anything else. You couldn’t get hired to work almost anywhere else. It’s like you were stuck going from one food job to another, but yeah, I started at a pizza place in high school. I started going to college. I needed health insurance so I went to work for Whole Foods Market. I worked for them. I eventually became a cheese buyer and then later a wine buyer for them.

I was working my way through college. Ended up I have BFA in painting and performance arts and then graduated from college. Tried to not work in food. That didn’t work out so well. Then I moved to New York and I really wanted to be like the great postmodern writer or write the great post post postmodern novel or become a great painter or whatever, but what I found when I moved here, it wasn’t exactly the way that I thought it was going to be as far as that goes, but I had to pay the bills so I got a job working at Dean & Deluca and then I got a job working at Murray’s and that lead me to work for the whole Andrew Tarlow King Luke empire thing, but once I moved here and started working in food, I realized that, “Oh, people did this.”

It wasn’t just what they did for money. People actually really enjoyed being a line cook or enjoyed selling cheese or enjoyed being a butcher. I don’t know. I think there was a real moment for me where I was like, “Oh, what I’ve been doing for work is really what I want to do with my life now

BAF: Was that due to partly the change in attitudes about food in the country with the advent of the celebrity chef?

Tom: Yes, the celebrity chef thing I think is definitely part of it, but really I think more than anybody, it’s Anthony Bourdain. His book really made working in food seem noble. The other thing was ultimately, there’s more creativity in food than there is almost in art. That was the other thing. I was like, “Oh, the art world is really political. There’s these brilliant people that never get shows and then there’s all these schlocky artists that do gimmicky bullshit and as opposed to food is really never ending.” You can keep going in any … just like wine in Italy. There’s 1400 different varietals, different grape varietals, let alone the different regions.

It’s like you can spend an entire lifetime trying to understand and know about wine in one small country, and that’s a small subset of the larger food thing, so there’s always more to learn, more techniques to figure out, more people to talk to and be shown things. It’s really, I think, one of the most fascinating vocations that one can choose if you’re interested in that sort of autodidactic kind of thing.

BAF: A butcher once told me he can’t find help. He said nobody wants to be a butcher anymore. I don’t know if you have the same issue here.

Tom: We were blessed with in New York right around 2009 when we opened The Meat Hook, butchering became sort of fashionable, so we haven’t really had nearly as hard of a time getting people interested in working for us. (We also pay pretty well and offer benefits and stuff. We’re pretty conscientious bosses.) For instance, our general manager, Sara Bigelow, number one, she’s a girl. Most people are kind of taken aback by the fact that about half of the people that work at the shop are women, but Sara Bigelow, she went to college and did that stuff and then got her first job with the college working in PR and then realized that she hated that cubicle culture and she heard about us and what we were doing. She was like, “Look, I’ll work for you for free. Just teach me how to do this.” She ended up being our first employee and now she runs the shop.

We have those kind of people from all kinds of backgrounds. We’ve had artists, writers, musicians, line cooks, all these different people who have decided, “Oh, this is what I want to do.”

BAF: What’s next?

Tom: I’m really interested in writing another book. I’m not quite there yet because I haven’t even gone and I need to do the book tour this summer. I’m really interested. I have some ideas for what I want to do, but I really want to go out into the wider world and see what people are interested in because I really want to do a book that people want to read, not just something you would hang another plaque on the wall, kind of like, “Oh, I wrote another book.” I really want to do something useful because I discovered in writing this book, writing a book is hard. It’s a lot of work and it’s a lot of stress and it’s a lot of anxiety. “Is anybody going to read this thing? Is it any good?”

I think what I’m sort of percolating on is I would really like to write a book about what I’m sort of calling the food of the 20th century and having it be a sort of region by region, like regional cooking of the United States in the 20th century kind of a thing. It’s harder and harder to find a mom and pop diner that isn’t using Sysco products.

I was really inspired by the old Sokolov book from the ‘80s called The Fading Feast that was basically about all those fading regional cooking styles, but we’ll see. I think it’s going to have a lot to with how well this book does. Maybe they won’t even let me back (laughing).

© 2014 Booksaboutfood.com

Dinosaur Ribs

MH Barbecue Sauce

Dinosaur Ribs

Serves 7 or 8

Special Equipment:

Butcher knife or large chef’s knife

Nonreactive food-safe container large enough to hold the ribs

Aluminum foil or a smoker

1 square-cut beef rib plate, 8 to 10 pounds

For the Marinade:

1 cup kosher salt

1 cup packed light brown sugar

1 cup soy sauce

One 6- to 8-ounce can pineapple juice

2 tablespoons freshly ground black pepper

Grated zest and juice of 1 lemon

2 teaspoons bonito flakes

1. To fabricate the ribs, take a bullnose butcher knife or large chef’s knife and cut the riblets off the bottom of the ribs at the joint where they meet.

2. Next, cut all the way through the space between the ribs with your knife, making sure that each rib has meat on it. Place the ribs in a large nonreactive food-safe container.

3. To make the marinade, combine the salt, brown sugar, soy sauce, pineapple juice, black pepper, lemon zest and juice, and bonito flakes and mix well in a medium bowl, using your hands to squish any lumps of sugar. Pour the mixture evenly all over the ribs and rub it in. Cover and refrigerate overnight. Set an alarm to wake up as early as you think you can.

4. When the alarm goes off, remove the ribs from the refrigerator and place them out at room temperature somewhere where they are unlikely to be molested by man or beast. Go back to bed.

5. When you wake up again, fire up your smoker or oven. You can cook the ribs at 220°F for 12 hours or at 250°F for 8 hours, depending on how early you got out of bed and what time you want to eat.

6. Put the ribs in (if using an oven, wrap them in foil first), sit back, and settle in for a day of lazily poking at the ribs. When the ribs are tender but not quite falling off the bone, they are ready.

7. Serve with the barbecue sauce, cold beer, and loud music.

MH Barbecue Sauce

Makes 3 cups

2 cups ketchup

1 cup water

1/2 cup cider vinegar

1/3 cup light brown sugar

1/3 cup granulated sugar

1 tablespoon freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon onion powder

1 tablespoon mustard powder, such as Colman’s

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

Combine all the ingredients in a non-reactive saucepan, bring to a simmer, and simmer gently for 11/2 hours. Remove from the heat and let cool for 45 minutes.

Stored in an airtight container in the refrigerator, the sauce will keep for up to

1 month. Freezing is not encouraged.

Excerpted from The Meat Hook Meat Book by Tom Mylan (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2014. Photographs by Michael Harlan Turkell. Illustrations by Kate Bonner.

Leave a Reply