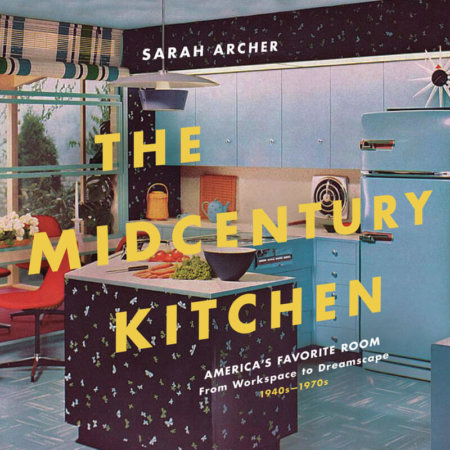

THE MIDCENTURY KITCHENAMERICA'S FAVORITE ROOM, FROM WORKSPACE TO DREAMSCAPE, 1940S-1970'S

An illustrated pop history from aqua to avocado, Westinghouse to Wonder Bread.

Nearly everyone alive today has experienced cozy, welcoming kitchens packed with conveniences that we now take for granted. Sarah Archer, in this delightful romp through a simpler time, shows us how the prosperity of the 1950s kicked off the technological and design ideals of today’s kitchen. In fact, while contemporary appliances might look a little different and work a little better than those of the 1950s, the midcentury kitchen has yet to be improved upon.

During the optimistic consumerism of midcentury America when families were ready to put their newfound prosperity on display, companies from General Electric to Pyrex to Betty Crocker were there to usher them into a new era. Counter heights were standardized, appliances were designed in fashionable colors, and convenience foods took over families’ plates.

With archival photographs, advertisements, magazine pages, and movie stills, The Midcentury Kitchen captures the spirit of an era—and a room—where anything seemed possible.

Sarah Archer is a writer and curator who specializes in design and material culture. The author of Midcentury Christmas and The Midcentury Kitchen, she contributes to Slate, The Atlantic, Architectural Digest, and newyorker.com. She lives in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Sarah Archer

Proust and his Madeleine are synonymous with food and memory. Most of us can certainly relate to the power of this experience. But no trip down the culinary memory lane would be complete without acknowledging the avocado green and aqua blue appliances, to name but two colors that were widely available at the time, that produced many a meal. Not to mention the matching wallpaper, telephone’s, bowls, and the omnipresent Jello mold, (Then at the height of their power and influence.) that made up the midcentury kitchen. Sarah Archer was recently kind enough to join us to chat about the the delight of such kitchens.

BAF: How did this whole idea come about?

Sarah Archer: That is a really good question, actually. It’s something that I’ve always been really interested in, so it’s almost like I just needed to gather the material and get a sense of where it fit in the bigger historical picture. The more I learned about industrialization and how the machines that are part of the story evolved and the utilities and the spreading of gas and water in cities, it all started to form this really interesting picture. And I just thought, “Now is the time.” My editor really liked it, liked the idea. That’s more or less how it happened. But it was just it’s always been something that fascinated me, and that time period in particular has always been really interesting to me.

BAF: What kind of kitchen you grew up in?

Sarah Archer: Yes. I basically grew up in a ’70s kitchen. I grew up on the Upper West Side in New York. And my parents had … actually still have, because it’s held up really, really beautifully … black Formica countertops. Nothing actually super colorful. It was just white appliances, which I’m now understanding may have been a little bit unusual for the time. But white appliances and really pretty oak cabinets, hardwood cabinets, which, I’m discovering, is a rarity, actually. Nowadays you must look at particle board. And fairly compact because it was a city kitchen, but with lots of kind of clever storage. So, that has given me the footprint for working myself in a relatively compact kitchen. And also being a little bit fascinated by that kind of suburban, mega kitchens that have evolved in recent decades, and I guess, to some extent, have their roots in the mid century as well.

BAF: White appliances back then, your parents were a little bit cutting edge, actually.

Sarah Archer: They may have been. Yeah, they didn’t go for harvest gold or anything. It was , yeah, I guess maybe they were going for black and white because that was a graphic option. I’m not really sure, actually. Maybe that was its own trend at the time. I should probably ask my mom about that. But yeah, black Formica, which is I have to say after 50 years it looks great. Still got it.

BAF: Colors are the one thing which really come to my mind first and foremost when I think of kitchens of this era.

Sarah Archer: Right, exactly. The funny thing is, too, that we were talking about this last night at the … We had a discussion. It was at me and Alexandra Lang who writes for Curved and Anastacia Marx de Salcedo who’s written about postwar food culture. She has a book called Combat-Ready Kitchen. We were talking about the color, if you want to say mood boards, of the different eras. General Motors owned Frigidaire, and they were showing model kitchens at Motorama. There was a lot of crossover between the design and marketing of appliances, major appliances, and of cars. And then that, of course, translated to things like linoleum flooring. And then we’re also in clothing and all sorts of other things. So, you can almost look at a blender, or a t-shirt, or a car from any given year and triangulate what the kitchen would look like, because those color trends were so powerful.

If you flipped through Architectural Digest or Veranda or any of the higher end interior shelter magazines, they do tend to be monochromatic in either in a very austere all white situation, or something more sort of vintagey looking that has kind of that sort of distressed wood or what have you. People are going less for those pops of wild color.

There are exceptions to that. Definitely like AGA stoves and certain enamel stoves from Europe that are popular, they’re very, very high end, very expensive. Come in a very wide array of colors. You can get a tangerine colored stove. Those run $20,000, $30,000. But generally speaking, if you’re looking at Home Depot and the regular places that most people get their fridge or their stove, it’s all pretty steel and maybe a slightly different color steel and that’s about it.

BAF: I know that the kitchen technology seemed to come more into play as the space race heated up. There were no computers, so the kitchen seemed to be the focal point of technology.

Sarah Archer: Yeah, that’s a good point. Nowadays When we talked about technology, it’s usually for the office, or for your car, or for your smartphone. There’s this kind of information exchange in that we relie on technology to make our households smarter in certain ways. People have smart thermostats and that kind of stuff. There are certainly refrigerators that have a transparent door that will tell you what’s inside. But the kind of gadgetry of the kitchen as the site of promise, of ‘in the future it will be like x, y, and z’. You’ll have all of these amazing things and your life will be totally transformed.

People don’t seem to be really that interested in that anymore, and there was a moment in the ’50s and ’60s when they really were. And that was a real selling point at world’s fairs, in department stores. There were promotional shorts that were futuristic and posited the kitchen as the site of even more progress in the home. And I think that’s partly because the progress that happened between, let’s say, the 1920s and the 1950s was huge. And part of that was all the electric and gas and water utilities becoming mainstream and becoming things that most people could rely on rather than just some people had. And the machines that would work off of those supplies became more and more affordable. It was kind of the stylish high tech locus in the home.

And I think the generation that witnessed that change was perhaps poised to expect even more change on that scale. Like if you were old enough to remember doing laundry by hand and shoveling coal into a cast iron stove and having to boil water every time you wanted to take a bath and all of that kind of stuff. Then suddenly you had a dishwasher, a gas range, and a refrigerator, you might well think, “Well gee, in 20 years maybe we’ll have … we will actually have robot maids like on The Jetsons. And when that didn’t happen, the interest shifted away from that and into the home office revolution and the desktop publishing revolution of the ’80s and ’90s.

Now when you look at kitchen design that’s really luxurious, it doesn’t tend to be futuristic. It tends to be almost more old fashioned, like real sumptuous materials. Not manmade materials, but real things like marble.People really like old fashioned light fixtures that are made with metal and glass and moving a little bit away from all the space age stuff and back to the materials of the teens and ’20s, which is kind of an interesting change.

BAF: Now we all want to go retro.

Sarah Archer: I think that to some extent that’s true. I think that one thing you see is that there’s a parallel between what’s going on in the food world and what’s going on in the kitchen design world. And that the trend for the old reliable design motifs, like people putting in black and white linoleum as kind of a retro touch, or even things like subway tile and milk glass lighting fixtures and brass hardware, things that are real … could be from a hundred years ago.

And they’re also getting into things like fermenting, as though that’s a new thing. It’s been rediscovered because a whole generation missed out on that, several generations. Like, “Oh, it’s this little thing that we don’t need to do that anymore because we have shelf stable food in cans.” But people are for taste reasons and nutritional reasons, and just because it’s kind of fun for some people who really love to do that kind of stuff, making things from scratch and being part of produce shares and fermenting their own food and all that kind of stuff.

So, it’s almost like the turn of the 20th century, all of those skills that were lost are coming back into the vogue, and that’s echoed in a sense, I don’t think deliberately necessarily. It just maybe things kind of cycle in and out, for similar reasons. There’s definitely a parallel, I think, between the two.

BAF: Would you say it was more status orientated or the most technologically advanced kitchen with the bright colors and things? Would that have been the trend back then?

Sarah Archer: Probably in the ’50s and ’60 I think definitely, yeah, because that was a sign that it was brand new. And having the latest colors just as in the car world or old or the fashion world, having the most recent, the last word in color and style, showed that maybe you could afford to replace everything or you could afford to redo it or redecorate in some sense. And if it was very dated, it gives you incentive to rip it out, which of course is good for the appliance makers because people say, “Oh, I’m sick of how this looks and I’m going to rip it out.” And then if they don’t really actually need a new stove. But there’s, yeah, definitely that kind of sense of novelty. It’s like, “Oh, this is the new fashionable color palette.”

Increasingly as the kitchen transformed from a workspace into an entertaining space. Because as a workspace, it didn’t really matter, right? It was just you wanted it to be clean, but you’re not having guests in there. If you have a great estate and you have staff working in your kitchen, you don’t actually hang out there in the teens and ’20s. But then as time goes on and people all across the social ladder are … either if they live in a one room apartment or they live in a great big house that has an open plan, people are increasingly entertaining in their kitchens. And maybe somebody will watch you cook and eat at the kitchen island. And that becomes part of … Dinner parties migrate from dining rooms into kitchens and kind of float around. And so, having a lovely kitchen or an eye catching stylish kitchen becomes part of the decor of the house.

BAF: You don’t really think of it. You don’t remember that people didn’t hang out in the kitchen, like you said.

Sarah Archer: Right. Right. Which people now I think in some sense don’t realize. That there’s this thing of everybody having the same kind of kitchen, more or less, and having the middle class version be the quote/unquote “normal version” is a relatively new idea. Basically, the options were that you either practically lived in your kitchen if you were living in a tenement or a farmhouse, or you had staff in your kitchen and you never really went anywhere near it. And the idea of it being … Those are now considered two extremes, but that used to be normal. And it’s not as though people would be elegantly entertaining at their coal stove. So, it completely the … The appliances being attractive is part of that.

BAF: Back in the day, was Formica the it material to use? Was that the trend7 material?

Sarah Archer: My sense is not that it was ever necessarily luxurious the way you might think of marble today, or the way I guess you probably would have thought of marble a hundred years ago. But that it was colorful in a way that no other countertop material ever had been before. It was originally marketed in the 1930s as a kind of workaround for lacquer. So, it was like the kind of like an inexpensive alternative to that.

And then it started to get developed into countertops when it was realized that it was very durable, and it was easy to clean, and it was sort of cheap. Not dirt cheap, but kind of relatively inexpensive way to add color and even pattern. Because there were lots of … There were Formica that was embedded with little sparkles. There were all sorts of different colors and patterns and the illusion of texture that you could do, and then match that with cabinets or contrast it or what have you.

And so, that, in and of itself, became a huge thing. And even things like putting in tiny offices inside kitchens that kind of became popular. Sort of the command center.

BAF: It’s interesting because The infamous Jello trend of that time seems to fit in nicely with the trend of the kitchen and the trend of all those Pyrex dishes.

Sarah Archer: Absolutely. Yeah, it almost aesthetically works together. The color of Pyrex and Tupperware and the kind of technicolor of Jello is aesthetically of a piece with itself. They kind of went together.

BAF: Did you have any ‘aha!’ moments or anything that really took you by surprise in researching?

Sarah Archer: That is a really great question. I think one of the things that I found really, really surprising is … and this is fairly early on when I started to first really get interested in the broader topic of kitchen design, going back even further in time … is that many of … not all, but many of the people who shaped what we now think of as the modern contemporary kitchen in terms of the way it’s laid out and defined were women. And they were, in some cases like that of Christian Frederick, they were professional home economists back when that was a thing. And some were architects ,like the Austrian architect Margarete Schutte-Lihotzky who was the first woman in all of Austria to qualify as an architect.

And they were both women in professions of various kinds who had been born in the 1880s or ’90s. And in their era, the idea … We would look at it and say, “Well, why do women necessarily belong there all the time in the first place? Can’t we do other things like design things, for instance?” And in their time, that was not a realistic expectation. There was no realistic expectation that you could transform the kitchen and then transform all of society and change everybody’s lives.

So, their goal was to make things easier for women in the kitchen, and that was really considered a form of feminism in its time. And nowadays we see that as being totally old fashioned and thinking like, “Well, the kitchen should be for everybody, and everybody can load their own stuff into the dishwasher, and it should be even, or evenly distributed.”

But I was really surprised at there was even a chemist who was working in the 1880s, I think, who had been … was a Vassar graduate. Ellen Richards Swallow, her name was. And who eventually worked at MIT. And her research, I think she was probably … she was the first, or if not the first, then one of the very earliest women to get a PhD in chemistry in the United States. And she devoted a lot of her research to cleaning and the chemistry of cleaning and home economics. That was the frontier for professional women at that time.

That’s what they knew, and that’s what they saw their mothers and grandmothers doing. And so, it seemed totally to reason that that’s what they would focus on and that it was even kind of a wild idea to think like, “Oh gee, we can make it better.”

What it puts into perspective I think, for me especially, is that I grew up in the ’80s as a kid. And so I was watching as many, many more women were going into the workforce full time. And I’m old enough to remember when that was a big change. Like it was the idea that if your mom works, that was like a cool, new thing that that was not necessarily expected. And I think nowadays it tends to be more expected. But it’s really not that long ago that that there was no expectation that that would happen.

So, the history of the kitchen is actually almost like in the last hundred years traces a lot of that other history. And they are kind of touchpoints in terms of who’s doing the cooking and who’s doing the washing up and whose job is it and all of those questions.

BAF: What are you working on next? What’s on the drawing board?

Sarah Archer: Actually, I’m working on two things right now, neither of which have to do necessarily … well, one of them kind of does with fifth century design. I’m working on a book about the culture of cats and cat ownership in Japan, and by which I mean the visual representation and cats as a cultural symbol and in cartoons and temples and figurines and Ukiyo-e prints and all that kind of stuff. And so, there’s lots of photography and artwork, antique artwork, going back to the 18th century.

And so, it’s a totally different topic. There’s very little mid century focus and lots of much older stuff and much newer stuff. It’s about the cat’s role as the symbol of good luck and how that differs from how they’re perceived in the west where we tend to think of them … people either love or hate them in the west, and they tend to be viewed as unlucky because of all the folklore about black cats, which is that kind of stuff. So, working on that now.

And I’m also proposing a book about the history of clutter, which is also a different left turn but concerns interiors.

Leave a Reply