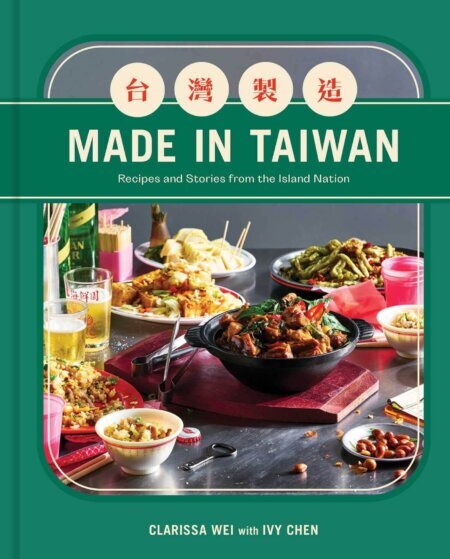

Made in TaiwanRecipes and Stories from the Island Nation

An in-depth exploration of the vibrant food and culture of Taiwan, including never-before-seen exclusive recipes and gorgeous photography.

Taipei-based food journalist Clarissa Wei presents Made in Taiwan, a cookbook that celebrates the island nation’s unique culinary identity—despite a refusal by the Chinese government to recognize its sovereignty. The expansive book contains deeply researched essays and more than 100 recipes inspired by the people who live in Taiwan today.

For generations, Taiwanese cuisine has been miscategorized under the broad umbrella term of Chinese food. Backed with historical evidence and interviews, Wei makes a case for why Taiwanese food should get its own spotlight. Made in Taiwan includes classics like Peddler Noodles, Braised Minced Pork Belly, and Three-Cup Chicken, and features authentic, never-before-seen recipes and techniques like how to make stinky tofu from scratch and broth tips from an award-winning beef noodle soup master.

Made in Taiwan is an earnest reflection of what the food is like in modern-day Taiwan from the perspective of the people who have lived there for generations. It is the story of a proud nation—a self-sufficient collective of people who continue to forge on despite unprecedented ambiguity.

Clarissa Wei is a freelance journalist based in Taipei. Born in Los Angeles but raised on the food of Taiwan, she has been writing about the cuisines and cultures of Taiwan and China for over a decade. Her writing has been published in The New York Times, The New Yorker, the Los Angeles Times, Serious Eats, and Bon Appétit. She has produced videos on cross-strait tensions for VICE News Tonight, 60 Minutes, and SBS Dateline. Previously, Clarissa was a senior reporter at Goldthread, a video-centric imprint of the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, where she made over 100 videos on the foods and cultures of China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan in the span of two years. In her spare time, she tends to a subtropical food forest on the outskirts of Taipei.

Clarissa Wei

Recently journalist and author Clarissa Wei as kind enough to answer some of our questions about Taiwanese food and her new book Made in Taiwan.

![]()

Can it be said that Taiwanese cooking is often overlooked?

Taiwanese cooking is definitely overlooked and is often grouped under the vast umbrella of Chinese cuisine.

Are there any unique characteristics about the food of Taiwan?

Our core condiments are unique to our island. Many of them were developed during the Japanese colonial era and the recipes have stayed the same since. Generally speaking, Taiwanese food errs towards the sweeter side of things.

Is there much regionality in Taiwanese food?

Yep. Especially in the old days, before the 90s. A lot of towns had their specialty dishes, but because of advanced infrastructure like a high-speed rail—which connects the top and bottom of the island in two hours— the regional lines have really blurred.

During the course of writing this book did you make any ‘discoveries’ about Taiwanese food that you didn’t know before?

So many. A major one is that the building blocks of our cuisine (i.e. the pantry items) are unique to the island.

You have done a wonderful job documenting some techniques. Was that part of the original concept of the book?

Yep. I wanted the book to be as thorough and comprehensive as possible.

How was the writing process for you? Did you enjoy it?

I’m a writer by trade so writing was the best part of the whole process.

How did you go about choosing the recipes?

I wanted the recipes to represent the major historical periods of Taiwan. We divided the book into themes and went from there.

What’s next for you?

I’d love to write another cookbook!

![]()

©2023 Booksaboutfood.com

“This is the story of a culture, a people, a community, a destiny, and an identity, told through recipes . . . alongside some of the best writing on the subject of all things Taiwanese. With Made in Taiwan, Clarissa Wei has created a true rarity: a deep dive that serves us on so many levels. Take a long swim in the superb food, clarity of exposition, exemplary storytelling, and inspiring insight. This book is a must-have for any home cook, food lover, culture geek, or curious reader.” —Andrew Zimmern, TV host

“Made in Taiwan is a tour de force. Clarissa Wei’s storytelling and photography are dazzling, her recipes irresistible. This magnificent, heartfelt book is essential to any Asian culinary library.” —Grace Young, author of Stir-Frying to the Sky’s Edge and The Breath of a Wok

“With the same curiosity and rigor that has permeated her work as a food writer and journalist, Clarissa Wei’s Made in Taiwan is a timely and deeply engrossing account of Taiwanese culinary and cultural history. As gorgeous as it is thorough, it’s the most affordable trip to Taiwan you can buy!” —Stephen Satterfield, founder of Whetstone Media, host of Netflix’s High on the Hog

“Clarissa has artfully woven food reporting with heartfelt storytelling, creating a truly special book on an important topic. In Made in Taiwan, she has given us the Taiwanese story to ponder, savor, and, ultimately, experience through cooking.” —Betty Liu, author of My Shanghai

“This book is a timely, joyful rewriting of the Taiwanese story, at a time when this island’s very identity hangs in the balance. Clarissa’s fascinating journalistic insights are matched by her great efforts to deconstruct recipes passed down through generations. It’s a book that I’ll keep on my kitchen shelf and look forward to referring to many, many times over the years.” —Isobel Yeung, VICE News correspondent

“To read Clarissa’s work is to feel her passion, her deeply rooted identity as a Taiwanese and Asian American, and her commitment to honoring the labor and culture of the people who feed us.” —Jenny Yang, stand-up comedian and actor

Fried Shrimp Rolls (蝦卷 – Xiā Juaˇn , 蝦卷 – Hê kńg)

Shrimp Rolls with Caul Fat

Sticky Rice Sausage (糯米腸 – Nuò Mˇı cháng, 大腸- Tuā Tnˆg)

Little Sausage in Big Sausage

![]()

Fried Shrimp Rolls (蝦卷 – Xiā Juaˇn , 蝦卷 – Hê kńg)

MAKES 10

These deep-fried seafood rolls are said to have been popularized in 1965 by a man named Chou Chin-Ken 周進根 in the Anping district of Tainan. A fish ball vendor by trade who sold shrimp rolls on the side, he became so known for the latter that he eventually rebranded his shop Chou’s Shrimp Rolls 周氏蝦捲, now a prominent restaurant chain with locations throughout the country. Tra- ditionally, the shrimp rolls are wrapped with caul fat—the lacey membrane that insulates the stomach of a pig. They’re dipped in a flour batter and then deep-fried at a high heat until crisp, light, and golden brown. The fat netting is the secret to a juicy roll, but because caul fat isn’t easily accessible, my recipe uses bean curd sheets instead.

1⁄2 pound (225 g) peeled and deveined shrimp, minced (see Notes)

1⁄4 cup (20 g) minced Taiwanese flat cabbage or green cabbage

1⁄4 cup (20 g) minced celery

2 ounces (60 g) ground pork

1 large egg, white and yolk divided

1 scallion, minced

1 teaspoon Taiwanese rice wine (michiu) or cooking sake

1 teaspoon toasted sesame oil

3 tablespoons tapioca starch or cornstarch, plus more for dusting

1 teaspoon white sugar

3⁄4 teaspoon fine sea salt

1⁄8 teaspoon ground white pepper

Packet of bean curd sheets (see Notes)

4 cups (1 l) canola or soybean oil

1⁄2 teaspoon wasabi paste

1 tablespoon Everyday soy Dressing (page 367)

To make the shrimp roll filling, pat the shrimp completely dry with a paper towel. In a bowl, combine the shrimp, cabbage, celery, ground pork, egg white, scallion, rice wine, sesame oil, tapioca starch, sugar, salt, and white pepper. Stir everything together with chopsticks in one direction until the mixture is very sticky, 1 to 2 minutes. Cover and put it in the refrigerator to firm up for 1 hour.

Take the bean curd sheets and cut them into 5 squares, about 8 x 8 inches (20 x 20 cm). Stack them on top of one another and cut across the diagonal to form 10 isosceles triangles. Moisten the sheets by laying a damp kitchen cloth on top of them for 30 seconds.

Lightly dust your work surface with tapioca starch. Put one triangle on your work surface with the top pointing away from you. The base should be the closest side to you. With a small pastry brush, brush a line of egg yolk on the left and right border of the triangle, so it looks like an upside-down V. With a

spoon, lay a row of filling, about 40 g, horizontally alongside the base of the triangle measuring 3 inches (7.5 cm) long and 1 inch (2.5 cm) wide. Leave a pinky-wide gap at the bottom. Fold in the bottom corners toward the center, and tightly roll the triangle away from you like it’s a burrito. Repeat with the remaining triangles and set aside on a tapioca starch–dusted plate.

In a large wok, heat the oil over medium-high heat until it reaches 325°F (160°C) on an instant-read thermometer. With tongs, carefully lower the shrimp rolls into the hot oil, and cook until they are golden brown and crisp on all sides, 3 to 4 minutes. Remove the rolls with tongs and drain over a paper towel–lined plate or a wire rack set in a rimmed baking sheet to drain.

In a small bowl, make a dipping sauce for the shrimp rolls by adding a small dollop of wasabi paste on top of the Everyday Soy Dressing. Enjoy the rolls while they’re still hot.

NOTES:

1 pound (450 g) shell-on shrimp will yield about 1⁄2 pound (225 g) peeled shrimp.

Bean curd sheets are sold dried, refrigerated, or frozen. They should be as thin as a piece of paper (in Taiwan, they’re like tissue paper). They’re also sometimes shaped like large, folded half-moons. If you get this type of sheet, just cut it directly into rough triangles. If you’ve procured tougher bean curd sheets that don’t soften after you’ve moistened them with a cloth, soak them in room- temperature water for a couple of minutes until they’re pliable. Do not use fresh bean curd sheets.

![]()

Shrimp Rolls with Caul Fat

MAKES 6

These caul fat–wrapped rolls are a tad larger than the versions made with bean curd sheets on the previous page, which is why this recipe makes six shrimp rolls instead of ten. The net volume for the filling, however, is exactly the same.

1⁄4 cup plus 3 tablespoons (105 ml) water

1⁄2 cup (60 g) cake flour

1⁄2 cup (60 g) tapioca starch or cornstarch

3 tablespoons canola or soybean oil

1⁄2 teaspoon baking powder

51⁄2 ounces (around 150 g in total weight) caul fat

fried shrimp roll filling (page 104)

1 tablespoon Everyday soy Dressing (page 367)

1⁄2 teaspoon wasabi paste

In a medium bowl, mix together the water, cake flour, tapioca starch, oil, and baking powder.

Cut the caul fat into 6 squares, about 6 x 6 inches(15 x 15 cm). Lay a row of shrimp filling, about 60 g, on the bottom of the square measuring 4 inches (10 cm) long and 1 inch (2.5 cm) wide. Leave a pinky-wide gap at the bottom. Fold the sides inward and roll the square away from you like it’s a burrito. Repeat with the remaining squares and set aside.

In a large wok, heat the oil over medium-high heat until it reaches 350°F (175°C) on an instant-read thermometer.

Give the batter a stir again. With your fingers, dunk a roll into the batter, let the excess drip off, and drop it into the hot oil. Cook until the roll is golden brown and crisp on all sides, 5 to 7 minutes. Remove the roll with tongs and drain over a paper towel–lined plate or a wire rack set in a rimmed baking sheet to drain. Repeat with the remaining rolls.

![]()

Sticky Rice Sausage (糯米腸 – Nuò Mˇı cháng, 大腸- Tuā Tnˆg)

These are usually sliced at a steep angle and served with soy paste, or cut in half lengthwise like a hot dog bun and stuffed with a Taiwanese pork sausage. As with many Taiwanese dishes, there’s quite a bit of variation to this. When the rice sausages are served à la carte, they’re made with thick and rubbery large intestines and flavored with peanuts. When they’re served at a night market stuffed with sausage, they’re made with paper-thin small-intestine casings. Within Taiwan, northerners like working with precooked rice and a lot more shiitake mushrooms, and southerners will stuff their casings with raw rice and keep the seasoning much simpler. Keeping true to both my heritage and Ivy’s, this recipe is inspired by the variants at southern Taiwanese night markets.

These are usually sliced at a steep angle and served with soy paste, or cut in half lengthwise like a hot dog bun and stuffed with a Taiwanese pork sausage. As with many Taiwanese dishes, there’s quite a bit of variation to this. When the rice sausages are served à la carte, they’re made with thick and rubbery large intestines and flavored with peanuts. When they’re served at a night market stuffed with sausage, they’re made with paper-thin small-intestine casings. Within Taiwan, northerners like working with precooked rice and a lot more shiitake mushrooms, and southerners will stuff their casings with raw rice and keep the seasoning much simpler. Keeping true to both my heritage and Ivy’s, this recipe is inspired by the variants at southern Taiwanese night markets.

MAKES 2 POUNDS

2 pounds (900 g) long-grain glutinous rice, also known as sticky rice

3 medium dried shiitake mushrooms

3 tablespoons lard or canola or soybean oil, plus more for pan-frying, divided

1⁄4 cup (20 g) fried shallots (store-bought or homemade; page 368)

1 tablespoon fine sea salt

1 teaspoon ground white pepper

Natural hog casing, soaked in warm water for 30 minutes and rinsed thoroughly

Rinse the glutinous rice under running water. In a large bowl, combine the glutinous rice with enough water to cover. Soak for 4 hours at room temperature or overnight in the refrigerator.

In a small bowl, cover the dried shiitake mushrooms with water, and soak until soft, about 1 hour. If you are in a rush, soak them in boiling water for 30 minutes (though they won’t be nearly as flavorful).

Drain the rice in a sieve and set aside. Squeeze out excess water from the shiitake mushrooms, then trim the stems and discard. Mince the caps and set aside.

Heat a wok over medium heat and add 1 tablespoon of the lard. When the lard has melted, add the mushrooms and cook, stirring, until it smells lovely, about 1 minute. Turn off the heat and transfer the cooked shiitakes to a large bowl. Add the rice, shallots, salt, white pepper, and the remaining 2 tablespoons lard, and mix to combine.

Using a good old-fashioned funnel and a stick, stuff the mixture into the natural hog casing by connecting the casing to the funnel and pushing the rice mixture through with a stick or the handle of a long wooden spoon. Shape the sausage into loose links, about 6 inches (15 cm) long and 1 inch

SPECIAL EQUIPMENT:

large funnel, cotton twine

NOTE:

You can also grill the sausages, which is how it’s traditionally done.

Little Sausage in Big Sausage

大腸包小腸

Dà cháng Bāo Xiaˇo cháng

MADE IN TAIWAN

248

Served like a hot dog, this dish is composed of a pork sausage wrapped in a rice sausage. To do this, first pan-fry the rice sausage until it’s slightly browned. Slice it lengthwise down the middle so it’s like a hot dog bun, and nestle the pork sausage inside. Season with some sautéed mustard greens and a sprinkle of sugar (page 53), thin slices of pickled cucumbers (page 83), raw garlic slices, and Everyday Garlic Soy Dressing (page 367).

(2 cm) thick, and tie a simple knot with a short cotton string in between each sausage to divide them up. It’s very important to keep the filling very loose and almost saggy; the rice will expand as it cooks later, and an overstuffed sausage might explode. With a toothpick, poke holes in the casings to release the air bubbles out of the sausages.

Bring a large pot of water to a slow simmer over low heat. Gently lower

the sausage links into the water and cook for 40 minutes. Remove and cool down. The sausage can be eaten as is or pan-fried. Any extras can be frozen for a couple of months.

TO PAN-FRY: Set a skillet over medium-high heat and add lard or oil (about 1⁄2 teaspoon for each sausage). When the lard is hot, add the sausage and cook, turning occasionally, until lightly browned, about 2 minutes. Remove from the heat and enjoy immediately.

Little Sausage in Big Sausage

大腸包小腸

Dà cháng Bāo Xiaˇo cháng

Served like a hot dog, this dish is composed of a pork sausage wrapped in a rice sausage. To do this, first pan-fry the rice sausage until it’s slightly browned. Slice it lengthwise down the middle so it’s like a hot dog bun, and nestle the pork sausage inside. Season with some sautéed mustard greens and a sprinkle of sugar (page 53), thin slices of pickled cucumbers (page 83), raw garlic slices, and Everyday Garlic Soy Dressing (page 367).

Leave a Reply